Commodity Atlas

Palm Oil

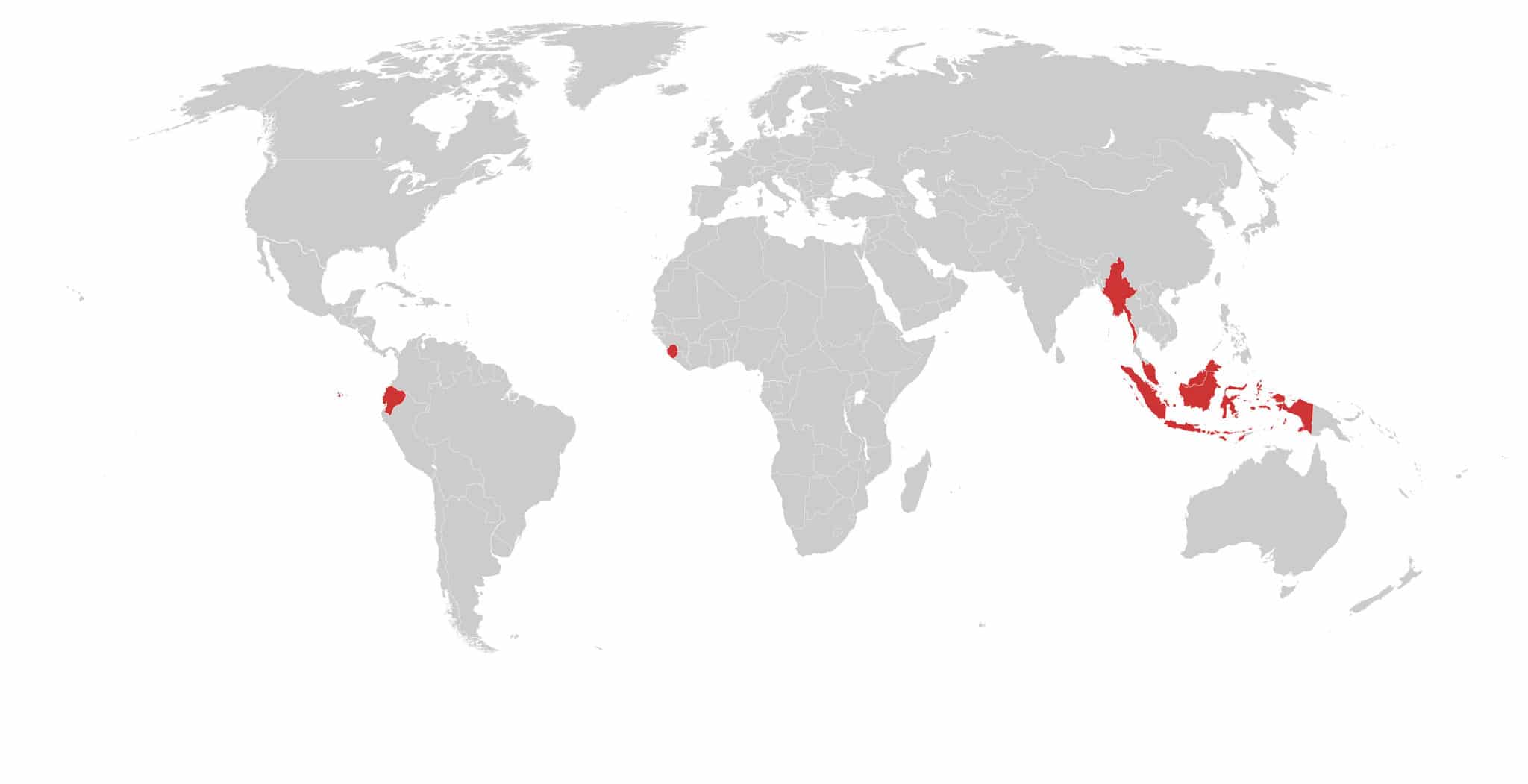

Countries Where Palm Oil is Reportedly Produced with Forced Labor and/or Child Labor

Palm oil is reportedly produced with forced labor (FL) and/or child labor (CL) in the following countries:

Burma (FL, CL)

Ecuador (FL, CL)

Indonesia (CL)

Malaysia (FL, CL)

Sierra Leone (CL)

Top ten countries that produce palm fruit worldwide (FAOSTAT 2017):

1. Indonesia

2. Malaysia

3. Thailand

4. Nigeria

5. Colombia

6. Ecuador

7. Cameroon

8. Ghana

9. Papua New Guinea

10. Honduras

Top ten countries that export palm oil worldwide (UN Comtrade 2018)1:

1. Indonesia

2. Malaysia

3. Netherlands

4. Papua New Guinea

5. Colombia

6. Guatemala

7. Germany

8. Honduras

9. Thailand

10. Ecuador

Top ten countries that import palm oil worldwide (UN Comtrade 2018)2:

1.India

2.China

3.Pakistan

4.Netherlands

5.Spain

6.United States of America

7.Bangladesh

8.Italy

9.Russian Federation

10.Egypt

1,2 International Trade Center (ITC Calculations based on UNCOMTRADE Statistics). https://www.intracen.org/

Where is palm oil reportedly produced with trafficking and/or child labor?

According to the U.S. Department of State 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report, palm oil is listed as being produced with forced labor or forced child labor in Burma, Ecuador, Indonesia, and Malaysia.[1b]

According to the U.S. Department of Labor 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, palm oil is produced with child labor in Indonesia and Sierra Leone and with forced labor and child labor in Malaysia.[2b]

Ecuador and Indonesia are listed as Tier 2 Countries by the U.S. Department of State 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report. Malaysia and Sierra Leone are listed as Tier 2 Watch List countries. Burma is listed as a Tier 3 country.[3]

Palm oil production and supply chain:

Palm can be grown on large plantations or in smallholder schemes. In Southeast Asia, most palm comes from large-scale plantations. Large palm oil companies, such as Kuala Lumpur Kepong (KLK), Sime Darby, and Wilmar, usually have their own plantations, mills, and processing plants.

In South America and Africa, the majority of palm comes from smallholder farms. Independent smallholders can seek out the highest available prices for mill purchase of their product; however, they may lack market access including credit for inputs. “Supported smallholders” are tied to mills through a variety of relationship models. Generally, they receive access to credit and/or technical assistance in return for a promise to sell their product. Specifics of these schemes are highly variable based on regional context.[21]

The oil palm is perennial and evergreen, making year-round production possible. After three years of applying herbicides and pesticides, weeding, and cultivating the growth of oil palm trees, workers must harvest the fruit. Ripe fruit is removed from trees by hand using a sharp tool such as a scythe or a long pole with a chisel. Loose fruits are also collected from the ground. A palm bunch can weigh 55 pounds and contain 3,000 fruits. Harvest periods typically last fewer than 48 hours, as fruit will begin to spoil.

The fruit is transported to mills after harvesting, where is it heat sterilized. This softens the fruit before it is separated from the bunch in a process called threshing. The kernels are collected and separated to be processed into palm kernel oil. The fruit is then passed on processing plants, where crude palm oil is produced from the flesh.[22] For every ten tons of palm oil, one ton of palm kernel oil is produced.[23] Crude palm oil may be further processed to produce derivatives of varying densities. The derivatives may also be blended with other vegetable oils.[24] One hectare of oil palm trees produce on average 3.8 tons of oil each year.[25] About sixty million tons of palm vegetable oil are produced every year.[26]

Examples of what governments, corporations, and others are doing:

In 2004, companies and other stakeholders created the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which has a certification system for sustainable palm oil. The RSPO developed standards for environmental and social responsibility, against which growers and millers are audited for certification. In As of 2018, the RSPO has a separate standard specifically for smallholders.[34] The RSPO has also piloted various interventions to support social and environmental sustainability programming. For example, the RSPO worked with technology provider Ulula to develop a streamlined grievance mechanism in 2018. In 2017, the RSPO worked with UTZ to develop a traceability system for certified palm oil.[35]

Approximately 19 percent of the world’s palm oil is certified by the RSPO. However, some stakeholders have called for stronger standards particularly around deforestation and the land rights of local communities.[36] The RSPO announced that after a 2018 review, standards would be strengthened around issues such as planting on peat, deforestation, and smallholder inclusion.[37] Civil society organizations have also noted that upholding any strengthened standards will also require strengthening of the auditing, grievance, and remediation processes, citing examples of RSPO inaction after revelations of labor rights abuses on member plantations.[38] These NGOs have specifically called for a strengthened labor rights monitoring approach to be integrated with proactive remediation of any issues identified.[39]

The Palm Oil Innovation Group (POIG) is a multi-stakeholder initiative that seeks to promote responsible palm oil production by building on the standards set by the RSPO. The POIG focuses on “environmental responsibility, partnerships with communities including workers’ rights, and corporate and product integrity.”[40] In 2017, POIG launched a charter for traders and processors of palm oil.[41] The charter states that processors and traders should assure compliance with POIG standards across their concessions, obtain independent verification, and publish a list of the plantations, mills, and refineries in their supply chains. The POIG membership charter also encourages members to support reform of RSPO monitoring procedures.[42]

Hamana Child Aid Society Sabah is an organization in the Malaysian state of Sabah on Borneo that focuses on educating the children of migrant workers employed in the palm oil industry. These children are extremely vulnerable to child labor because they lack legal documents and are therefore unable to attend school. Hamana Child Aid Society Sabah runs 128 learning centers with a total of 12,000 students. The organization is funded by foreign donors, including the European Union.[43]

What does trafficking and/or child labor in

palm oil production look like?

Human trafficking and labor rights abuses in the palm oil sector are driven by transnational and domestic migration, as well as displacement of local farmers near plantations. Workers in oil palm plantations are particularly vulnerable to modern slavery because of the isolation of palm groves.[4] Common labor abuses include long working hours, passport confiscation, induced indebtedness, contract substitution, and non-payment and underpayment of wages.[5]

Research by organizations such as the Fair Labor Association and Verité has found that workers in palm oil plantations face significant vulnerability, patterns of abuse and malpractice, and coercion at various stages of the recruitment, migration and employment process. Long hours, extremely low wages, and physically demanding jobs leave workers susceptible to workplace injuries and poor general health. Many workers are undocumented and face the threat of being denounced to authorities, risking detention and deportation.[6]

The Malaysian palm industry relies heavily on migrant workers from Indonesia, Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Nepal, many of whom are recruited by third-party labor brokers.[7] On Malaysian plantations, some employers take possession of workers’ visas, passports, and work permits, thus restricting the workers’ ability to leave the plantations.[8] The ILO reported widespread non-compliance by licensed recruiters with legal and policy frameworks, few enforced penalties, systemic illegal recruitment, and the use of recruitment fees.[9]

Rather than foreign migrant workers, in Indonesia, most palm oil workers are domestic migrants to the Kalimantan and Sumatra regions. Research by the Fair Labor Association published in 2018 linked forced labor risk to high quota targets that incentivized use of unpaid family labor as well as “low wages, remote locations of plantations, limited mobility of workers; and lack of contractual agreements.”[10] Many workers interviewed by Amnesty International documented cases of foremen threatening to take deductions from wages in order to pressure workers to fill their quotas. [11]

The U.S. Department of State 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report notes that in Burma, local labor traffickers recruit men and boys into forced labor on palm oil plantations.[12] Some migrant workers on these plantations experienced debt bondage and had had their wages withheld for one year. Their subsequent low wages had left them unable to return home for over a decade.[13]

According to the The U.S. Department of State 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report, Indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorians, Colombian refugees, and children are the most vulnerable to trafficking in the Ecuadoran palm oil sector.[14] Verité research also identified deceptive labor recruitment practices that disproportionately affect Columbian migrants and refugees in Ecuador. Labor recruiters misrepresented the working and living conditions on palm plantations, and they were lured into jobs with far worse pay and conditions than expected. Palm workers were reportedly paid as little as a sixth of the amount originally promised to them and were forced to work overtime, sometimes without pay. Workers also faced limits on their freedom of movement and communication, including curfews, constant surveillance, and supervision by armed guards. Workers depended on their employers not only for their incomes, but also for food and shelter, which restricted workers’ ability to leave. Furthermore, some workers fell into debt due to deductions for food and housing that were often of poor quality. Some employers withheld workers’ wages and threatened workers with physical violence, reporting undocumented workers to authorities, and the worsening of already poor working conditions in order to prevent them from seeking assistance or protesting unfair treatment.[15]

Child labor in palm oil production is typically tied to low wages and social exclusion of migrant families. For example, children of undocumented workers are at a higher risk of labor exploitation on palm plantations, particularly in Malaysia’s territory on the island of Borneo. There is evidence of weaker enforcement of labor laws in this area.[16] Child labor is reportedly a risk across Indonesia’s agricultural plantation industries, including production and harvest of palm oil, which includes growing, fertilizing, cutting, spraying, collecting, and loading palm oil fruits.[17] The children of plantation workers are particularly vulnerable to child labor, due to poverty, poor access to education, remoteness, and social exclusion.[18] In worker interviews conducted by Amnesty International in 2016, some children were found to have dropped out of school to help their parents by working on the plantations for all or most of the day.[19] Children tend the nursery and collect fallen palm fruitlets to help adult laborers, often their parents, meet their quotas and earn premium pay.[20]

Palm oil – or its derivatives – is present in up to 50 percent of all products in grocery stores.[27] Sometimes labeled in products as “vegetable oil,” it is used in products including fuels, soaps and shampoos, processed foods, cereals, baked goods, margarine, cosmetics, confectionary items, cleaning products, detergents, toothpaste, and candles. From 1995 to 2015, the global production of palm oil has quadrupled. This has been attributed to the use of vegetable oils in consumer products, as well as an increasing demand for biodiesel fuels in developed countries. Three billion people in 150 countries use products that contain palm oil.[28]

Growth in India and China contributes to the ever-increasing demand for oil, which the World Wildlife Fund reports may double by 2020.[29]

Environmental consequences

of palm oil production:

Palm oil production is linked with substantial environmental consequences, notably through widespread deforestation, which leads to the destruction of habitats for endangered species, such as orangutans, and contributes to climate change.[30] Approximately 16,000 square miles of rain forest on the island of Borneo have been destroyed through logging, burning, and bulldozing in order to produce palm oil since 1973.[31] As palm production spreads to Latin America and Africa, deforestation is increasing in palm-producing regions. Greenpeace has described the company Herakles Farms in Cameroon as illegally logging and clearing forest.[32] Oxfam has stated that the deforestation resulting from the conversion of forest to farmland in Indonesia would require “420 years of biofuel production to pay back the carbon debt.”[33]

LEARN MORE

Endnotes

[2b] U.S. Department of Labor. 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. 2018 https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ilab/ListofGoods.pdf

[3] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2019. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-Trafficking-in-Persons-Report.pdf

[4] The Consumer Goods Forum Fair Labor Association. Assessing Forced Labor Risks in the Palm Oil Sector in Indonesia and Malaysia. November 2018. https://www.theconsumergoodsforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/201811-CGF-FLA-Palm-Oil-Report-Malaysia-and-Indonesia_web.pdf

[5] Eurasia Review. Trafficking In Persons And Forced Labor: Southeast Asian Scenario – Analysis. July 24, 2017. https://www.eurasiareview.com/24072017-trafficking-in-persons-and-forced-labor-southeast-asian-scenario-analysis/\

U.S. Department of Labor. 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. 2018 https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ilab/ListofGoods.pdf

[6] Verité. Labor and Human Rights Risk Analysis of Ecuador’s Palm Oil Sector. May 2016. https://verite.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Risk-Analysis-of-Ecuador-Palm-Oil-Sector-Final.pdf

Fair Labor Association. Assessing Forced Labor Risks in the Palm Oil Sector in Indonesia and Malaysia. November 2018. https://www.fairlabor.org/sites/default/files/documents/palm_oil_report_fla-cgf_final.pdf

[7] International Labor Rights Forum. Certifying Exploitation: Why “Sustainable: Palm Oil Production is Failing Workers. 2018. https://laborrights.org/sites/default/files/publications/NLFGottwaldPalmOil.pdf

[8] Fair Labor Association. Assessing Forced Labor Risks in the Palm Oil Sector in Indonesia and Malaysia. November 2018. https://www.fairlabor.org/sites/default/files/documents/palm_oil_report_fla-cgf_final.pdf

[9] International Labor Organization. The Migrant Recruitment Industry: Profitability and unethical business practices in Nepal, Paraguay and Kenya. 2017. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/fair-recruitment/WCMS_574484/lang–en/index.htm

[10] Fair Labor Association. Assessing Forced Labor Risks in the Palm Oil Sector in Indonesia and Malaysia. November 2018. https://www.fairlabor.org/sites/default/files/documents/palm_oil_report_fla-cgf_final.pdf

[11] UNICEF. Palm Oil and Children in Indonesia: Exploring the Sector’s Impact on Children’s Rights. 2016. https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/Palm_Oil_and_Children_in_Indonesia.pdf

[12] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2019. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-Trafficking-in-Persons-Report.pdf

[13] Yan, Wudan. These Burmese palm oil workers say they’re trapped on plantations. Public Radio International. May 2017. https://www.pri.org/stories/2017-04-10/these-burmese-palm-oil-workers-say-theyre-trapped-plantations

[14] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2019. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-Trafficking-in-Persons-Report.pdf

[15] Verité. Labor and Human Rights Risk Analysis of Ecuador’s Palm Oil Sector. May 2016. https://verite.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Risk-Analysis-of-Ecuador-Palm-Oil-Sector-Final.pdf

[16] The Forest Trust. Children in the Plantations of Sabah. 2017. https://www.earthworm.org/uploads/files/Children-in-Plantations-of-Sabah-2017-report.pdf

[17] United States Department of Labor. List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. September 30, 2018. https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ilab/ListofGoods.pdf

[18] UNICEF. Palm Oil and Children in Indonesia: Exploring the Sector’s Impact on Children’s Rights. 2016. https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/Palm_Oil_and_Children_in_Indonesia.pdf

[19] Amnesty International. Case studies: Palm oil and human rights abuses. November 2016. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/11/case-studies-palm-oil-and-human-rights-abuses/

[20] Amnesty International. The Great Palm Oil Scandal. 2016. https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/ASA2151842016ENGLISH.PDF

[21] Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). Smallholder Oil Palm Growers In Latin America. The Proforest Initiative. 2018. https://www.rspo.org/publications/download/4108b98b039fca5

[22] The Forest Trust. Palm oil: the process from tree to refinery. 2013. https://www.tft-earth.org/stories/blog/palm-oil-the-process-from-tree-to-refinery/

[23] Malaysian Palm Oil Council. Processing Flow Chart. https://www.mpoc.org.my/Processing_Flow_Chart.aspx

[24] GreenPalm. What is Palm Oil Used In? https://www.greenpalm.org/en/about-palm-oil/what-is-palm-oil-used-in

[25] European Palm Oil Alliance. What is palm oil? https://www.palmoilandfood.eu/en/what-is-palm-oil

[26] FAOSTAT. 2014. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/?#data/QD

[27] Rainforest Alliance. Palm Oil Fact Sheet. https://www.ran.org/palm_oil_fact_sheet/

[28] Tullis, Paul. How the world got hooked on palm oil. The Guardian. February 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/feb/19/palm-oil-ingredient-biscuits-shampoo-environmental

[29] World Wildlife Fund (WWF). About Palm Oil. https://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/footprint/agriculture/palm_oil/

[30] Greenpeace. Herakles Farms in Cameroon: A Showcase in Bad Palm Oil Production. 2013. https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/Global/usa/planet3/PDFs/Forests/HeraklesCrimeFile.pdf

[31] Hillary Rosner. “Palm oil is unavoidable. Can it be sustainable?” National Geographic. December 2018. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/12/palm-oil-products-borneo-africa-environment-impact/

[32] Greenpeace. Herakles Farms in Cameroon: A Showcase in Bad Palm Oil Production. 2013. https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/Global/usa/planet3/PDFs/Forests/HeraklesCrimeFile.pdf

[33] Oxfam. Another Inconvenient truth: How Biofuel Policies are Deepening Poverty and Accelerating Climate Change. June 26, 2008. https://www.oxfam.org/en/grow/policy/another-inconvenient-truth

[34]Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. History and Milestones. https://rspo.org/about#history-and-milestone

[35]Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. PalmTrace. https://rspo.org/palmtrace

[36] Investor Letter Regarding RSPO Principle’s and Criteria Review, ESG Factors for Integration in 2nd Consultation. August 2018. https://www.ceres.org/sites/default/files/Letters/RSPO%20P%26C%20Review%20Investor%20Letter_08.01.2018.pdf

[37] Food Navigator. RSPO Standards Undergo Major Review. November 2018. https://www.foodnavigator-asia.com/Article/2018/11/19/RSPO-certification-standards-undergo-major-review-Top-expert-takeaways-from-the-most-consultative-review-process-ever#

[38] Rainforest Action Network. NGOs Call for Systemic Reforms to RSPO Certification Scheme Beyond Standards Review. 2017. https://www.ran.org/press-releases/ngos_call_for_systemic_reforms_to_rspo_certification_scheme_beyond_standards_review/

[39] Rainforest Action Network. NGOs Call for Systemic Reforms to RSPO Certification Scheme Beyond Standards Review. 2017. https://www.ran.org/press-releases/ngos_call_for_systemic_reforms_to_rspo_certification_scheme_beyond_standards_review/

[40] Palm Oil Innovation Group (POIG). https://poig.org/

[41] Palm Oil Innovation Group (POIG). POIG Traders and Processors Charter. https://poig.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/271117_POIG-Traders-Processors-Charter.pdf

[42] Food Navigator. POIG Publishes Charter for Sustainable Palm Oil Processors. 2017. https://www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2017/12/11/POIG-publishes-charter-for-sustainable-palm-oil-processors

[43] Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. https://www.rspo.org/members/216/borneo-child-aid-society