Commodity Atlas

Tea

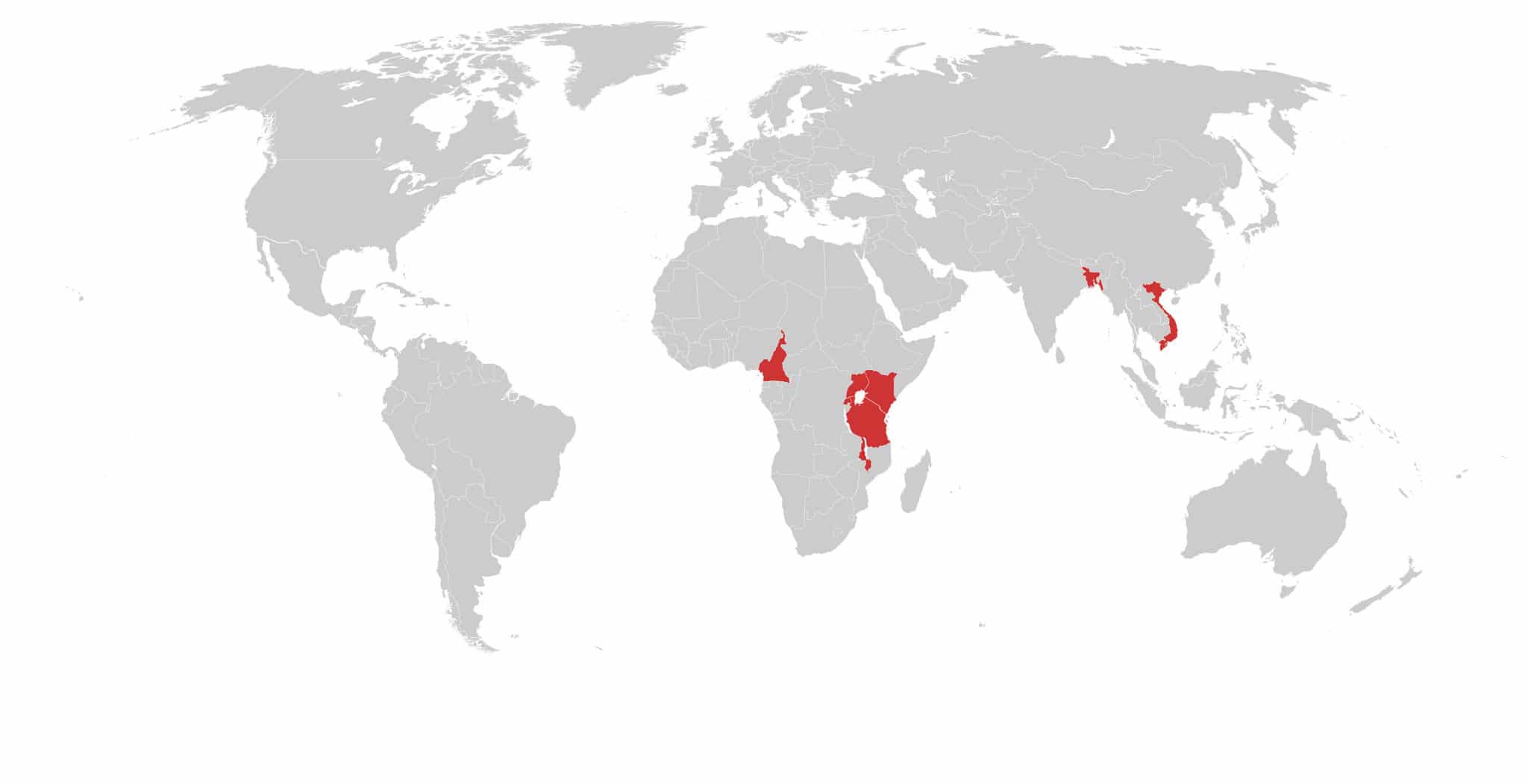

Countries Where Tea is Reportedly Produced with Forced Labor and/or Child Labor

Tea is reportedly produced with forced labor (FL) and/or child labor (CL) in the following countries:

Bangladesh (FL)

Cameroon (FL)

Kenya (CL)

Malawi (CL)

Rwanda (CL)

Tanzania (CL)

Uganda (CL)

Vietnam (CL)

Top ten countries that produce tea worldwide (FAOSTAT 2017)1:

1. China

2. India

3. Kenya

4. Sri Lanka

5. Vietnam

6. Turkey

7. Indonesia

8. Burma

9. Iran

10. Bangladesh

Top ten countries that export tea worldwide (UN Comtrade 2018)2:

1. China

2. Kenya

3. India

4. Sri Lanka

5. Germany

6. Poland

7. Japan

8. United Kingdom

9. United States of America

10. Vietnam

Top ten countries that import tea worldwide (UN Comtrade 2018)3:

1. Pakistan

2. Russia

3. United States

4. United Kingdom

5. Egypt

6. Germany

7. Morocco

8. Japan

9. Vietnam

10. France

[1] FAO. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC

[2,3] International Trade Center (ITC Calculations based on UNCOMTRADE Statistics). https://www.intracen.org/

Where is tea reportedly produced with trafficking and/or child labor?

The U.S. Department of State 2018 Trafficking in Persons Report notes that forced labor or forced child labor is present in tea production in Bangladesh and Cameroon.[1b]

According to the U.S. Department of Labor 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, tea is produced with child labor in Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and Vietnam.[2b]

There is some evidence that workers on Indian tea plantations face indicators of forced labor.[3b]

The U.S. Department of State 2018 Trafficking in Persons Report lists Cameroon, Malawi, Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Vietnam as Tier 2 countries. Bangladesh is listed as a Tier 2 Watch List country.[4]

Tea production and supply chain:

Tea is produced on both smallholders and larger commercial plantations or estates.[24] There is no precise data about the scale of production on small farms versus estates, but small farms appear to be more prevalent in Africa than in tea producing regions in India and Sri Lanka. The type of production influences the type of labor utilized. Small-scale farmers typically may rely more heavily on family labor, but there appears to be use of hired/waged labor as well, at least in some regions, particularly during peak harvest periods.[25] Commercial estates utilize hired labor, but among these workers, there is likely to be heterogeneity in status: some may be permanent, some may be temporary and some may be casual or hired by a third party labor provider.[26]

Many of the activities involved in tea production are labor intensive. These activities might include preparing land, transplanting seedlings, applying mulch, applying fertilizer, manual weeding, and leaf plucking.[27] Leaf harvesting generally represents a peak in manual labor, leading many plantations to hire temporary workers.[28] Tea is harvested year-round, but high season depends on the exact region and type of tea.[29]

Tea is usually processed in the countries of origin because processing must begin relatively quickly after harvest. Tea is processed at processing plants, which may be part of medium and large-scale plantations. After processing, tea is sold to tea companies through brokers.[30] The tea companies blend the tea and sell to retailers.[31]

Examples of what governments, corporations, and others are doing:

The Ethical Tea Partnership (ETP) is an alliance of member tea companies that works to promote social and environmental standards in members’ supply chains. In addition, ETP has programs around livelihood improvement for workers and smallholders. As an example of livelihood programming, the ETP partnered with IDH to improve quality and productivity, as well as market access, for smallholder farmers in Indonesia. The project also made USD 150,000 available for loans to small producers.[33]

On some Bangladeshi tea plantations in the northeast tea-growing region Sylhet, living and working conditions have improved after the installation of water pumps and latrines. Bangladesh’s 165 tea plantations employ around 400,000 workers, and many of them lack basic hygiene and sanitation practices. Pumps and latrines were installed by international NGO, WaterAid, and their local partner, the Institute of Development Affairs (IDEA), after negotiations with the plantations’ management.[34]

In 2017, UNICEF Rwanda adopted an industry approach to connect with the private sector and signed an agreement with Rwanda’s National Agricultural Export Development Board (NAEB) to end child labor in the tea industry.[35] Focal persons from 16 companies and 20 cooperatives were oriented on the Children’s Rights and Business Principles (CRBP), along with 70 employees from various private sector companies. The UN agency brought expertise and trained staff from Rwanda’s tea sector, hoping to improve the welfare of children and mothers in Rwanda.

In May 2018, the Traidcraft Exchange launched the “Who picked my tea?” campaign which encouraged large U.K. tea companies to publish lists of their suppliers in India. As of 2019, six major U.K. tea brands have published full supplier lists noting the estates in India that supply their tea. The campaign is designed to draw attention to women workers on tea estates and to ultimately improve their living and working conditions.[36]

How do Trafficking and/or Child Labor in Tea Production Affect Me?

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, tea is the second most consumed beverage in the world, trailing only water. In the United States in 2018, 3.8 billion gallons of tea were consumed.[32]

What does trafficking and/or child labor in

tea production look like?

According to the U.S. Department of State, “ethnic Indian families are forced to work in the tea industry in the northeastern part of [Bangladesh].”[5] Indian tea accounts for a quarter of global production, and the industry employs 3.5 million workers on plantations, many of whom are internal migrants.[6] Tea estate owners in Assam, India reportedly compensate workers, at least partially, through the provision of “in kind” benefits such as housing, health facilities, schools, and food rations in addition to a daily wage. In some cases, however, these services and benefits are either not provided at all or the housing that is provided results in sub-standard living conditions.[7] A report published in 2018 by the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI) found that 47 percent of workers in their study did not have access to potable water, 26 percent did not have access to a toilet, and 24 percent did not have reliable electricity. These workers earned approximately USD 2.00 per day.[8] A 2014 report from the Columbia Law School Human Rights Institute noted significant indicators of forced labor on Indian tea plantations, such as punitively high quotas and wage deductions. Workers reported the necessity of subcontracting work to meet quotas and facing substantial wage deductions.[9] The low wages and poor conditions on these tea plantations have reportedly led to children living on tea plantations or in surrounding areas being targeted for trafficking to urban areas.[10] The 2018 SPERI report further documented penalties for not meeting daily quotas, unpaid labor, deductions for services that were not provided, deductions for services that are supposed to be offered freely, fees for banking, and non-payment of wages (sometimes punitively) on Indian tea plantations in Assam and Kerala.[11] Exploitation is sometimes accompanied by physical violence, threats, verbal abuse and/or sexual violence.[12] The dynamic of estate owners providing in kind benefits to tea workers makes them both reliant on the estate and vulnerable to exploitation.[13]

Workers also experience debt.[14] Siddharth Kara, in Bonded Labor: Tackling the System of Slavery in South Asia, describes victims of human trafficking in the tea industry as typically poor and indebted to their employers.[15] Employers seek to generate revenue by lending money or providing services to workers and charging high interest on debts, leading to debt bondage.[16] Those who take out loans experience higher levels of abuse and exploitation. These bonded laborers are often women and their children who have no choice but to accompany their parents in the fields. Aging parents are incentivized to put their children to work in order to meet strictly enforced tea picking quotas and to make use of their children’s dexterity, which is necessary for weeding fields and picking tea leaves.[17] In tea production, children are usually employed in the fields to weed, hoe, or to work in nurseries.[18]

There have been anecdotal reports of trafficked migrant laborers and poor working conditions in a number of sub-Saharan African tea-producing countries. Seasonal temporary workers, who are more common than permanent workers, are often paid in piece-rate. Permanent workers receive higher wages and have access to benefits such as housing and medical care, but often struggle to make a living wage nonetheless, especially on small-scale farms.[19] Piece-rate and low wages often require families to bring their children to work. Child labor has been reported on small-scale farms in Rwanda, where children reportedly engage in all levels of tea production. In Kenya, children account for an estimated 15 percent of all tea sector workers.[20] A BBC investigation in early 2016 found child labor on a tea plantation in Uganda, where children carried seedlings up a steep hill and weeded rows.[21]

A UN report on Uganda’s tea sector anecdotally estimated that migrant workers make up 40 to 60 percent of the sector’s workforce, since work on tea estates is regarded by local Ugandans in tea-growing regions as undesirable. Migrant workers come from other districts of Uganda, as well as from Rwanda.[22] A December 2016 news report in Uganda reported that 43 Rwandans were arrested after being “trafficked” into the country for work on tea plantations, although it is unclear whether the Rwandans were trafficked or rather voluntarily migrated without correct documentation.[23]

LEARN MORE

- Read a United Nations Conference Report on Trade and Development summarizing the global tea trade.

- Watch a CNN Freedom Project video about child labor, debt bondage, and human trafficking in tea production.

- Watch a BBC investigation video on living conditions on tea estates in Assam, India, by Justin Rowlatt.

- Read a report on working and living conditions for women on tea estates in Assam, India.

Endnotes

[1] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[2] U.S. Department of Labor. List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. 2018

https://www.dol.gov/ilab/reports/child-labor/list-of-goods/

[3] Columbia Law School Human Rights Institute. “The More Things Change …” The World Bank, Tata and Enduring Abuses on India’s Tea Plantations. January 2014. https://web.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/microsites/human-rights-institute/files/tea_report_final_draft-smallpdf.pdf

[4] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[5] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[6] Nagaraj, Anuradha. “British brand Clipper promises slave-free tea.” Reuters. November 15, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-slavery-tea/british-brand-clipper-promises-slave-free-tea-idUSKCN1NK2R5

Raj, Jayaseelan. “The hidden injuries of caste: south Indian tea workers and economic crisis.” Open Democracy. June 29, 2015. https://www.opendemocracy.net/beyondslavery/jayaseelan-raj/hidden-injuries-of-caste-south-indian-tea-workers-and-economic-crisis

[7] Traidcraft Exchange. The Estate They’re In: How the tea industry traps women in poverty in Assam. May 2018. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59242ebc03596e804886c7f4/t/5b27a6270e2e72364827f389/1529325117476/The+Estate+They%27re+In.pdf

[8] LeBaron, Genevieve. The Global Business of Forced Labor. Sheffield Political Economy Institute. 2018 https://globalbusinessofforcedlabour.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Report-of-Findings-Global-Business-of-Forced-Labour.pdf

[9] Columbia Law School Human Rights Institute. “The More Things Change …” The World Bank, Tata and Enduring Abuses on India’s Tea Plantations. January 2014. https://web.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/microsites/human-rights-institute/files/tea_report_final_draft-smallpdf.pdf

[10] Basu, Anasuya S. “Assam’s tea gardens become hunting ground for child traffickers.” Hindustan Times. September 3, 2015. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india/assam-s-tea-gardens-become-hunting-ground-for-child-traffickers/story-MLuOTlMOheHKBpw8FDro1I.html

Chamberlain, Gethin. “How poverty wages for tea pickers fuel India’s trade in child slavery.” The Guardian. July 20, 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jul/20/poverty-tea-pickers-india-child-slavery

[11] LeBaron, Genevieve. The Global Business of Forced Labor. Sheffield Political Economy Institute. 2018 https://globalbusinessofforcedlabour.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Report-of-Findings-Global-Business-of-Forced-Labour.pdf

[12] LeBaron, Genevieve. The Global Business of Forced Labor. Sheffield Political Economy Institute. 2018 https://globalbusinessofforcedlabour.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Report-of-Findings-Global-Business-of-Forced-Labour.pdf

[13] Traidcraft Exchange. The Estate They’re In: How the tea industry traps women in poverty in Assam. May 2018. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59242ebc03596e804886c7f4/t/5b27a6270e2e72364827f389/1529325117476/The+Estate+They%27re+In.pdf

[14] Traicraft Exchange. The Estate They’re In: How the tea industry traps women in poverty in Assam. May 2018. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59242ebc03596e804886c7f4/t/5b27a6270e2e72364827f389/1529325117476/The+Estate+They%27re+In.pdf

[15] Kara, Siddharth. Bonded labor: Tackling the System of Slavery in South Asia. Columbia University Press. 2012.

[16] LeBaron, Genevieve. The Global Business of Forced Labor. Sheffield Political Economy Institute. 2018 https://globalbusinessofforcedlabour.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Report-of-Findings-Global-Business-of-Forced-Labour.pdf

[17] Kara, Siddharth. Bonded labor: Tackling the System of Slavery in South Asia. Columbia University Press. 2012.

[18] ActionAid. For the Rights of Tea Workers in Assam. https://www.actionaid.org/india/what-we-do/assam/rights-tea-garden-workers-assam

[19] van der Wal, Sanne. Sustainability Issues in the Tea Sector. SOMO. June 1, 2008. https://www.somo.nl/sustainability-issues-in-the-tea-sector/

[20] Sustainable Trade Initiative (IDH). The True Price of Tea from Kenya. May 5, 2016.

[21] O’Dowd, Vinnie and Danny Vincent. “Catholic Church linked to Uganda child labour.” BBC News. January 5, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-35220869

[22] UN Capital Development Fund. Uganda’s Tea Payments Profile. July 2015. https://www.uncdf.org/article/3403/digital-financial-services-in-uganda-ugandas-tea-payments-profile

[23] Kakogoso, Vanansio. “43 Rwandans arrested in Kabale being trafficked to unknown destination.” MK News Link. December 14, 2016. https://mknewslink.com/2016/12/14/43-rwandans-arrested-kabale-trafficked-unknown-destination/

[24] United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Contribution of tea production and exports to food security, rural development and smallholder welfare in selected producing countries. 2013. https://www.fao.org/3/a-i4485e.pdf

[25] Gonza, M.J. and P. Moshi. Tanzania Children Working in Commercial Agriculture – Tea: A Rapid Assessment. International Labour Organization International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC). January 2002. https://staging.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/2002/102B09_28_engl.pdf

Perera, Prasanna. Tea Smallholders in Sri Lanka: Issues and Challenges in Remote Areas. International Journal of Business and Social Science, Vol. 5, No. 12. November 2014. https://ijbssnet.com/journals/vol_5_no_12_november_2014/13.pdf

Cramer, Christopher, Deborah Johnston, Carlos Oya and John Sender. Fairtrade, Employment and Poverty Reduction in Ethiopia and Uganda. Fair Trade, Employment & Poverty Reduction Research. April 2014. https://ftepr.org/wp-content/uploads/FTEPR-Final-Report-19-May-2014-FIN

[26] Thapa, Namrata. Employment Status and Human Development of Tea Plantation Workers in West Bengal. NRPPD Discussion Paper. 2012. https://www.cds.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/NRPPD11.pdf

Fairtrade Foundation. Tea Farmers and Workers. https://www.fairtrade.org.uk/en/farmers-and-workers/tea

[27] International Labor Organization – IPEC. Hazardous Labor in Agriculture: Tea. https://www.ilo.org/public//english/standards/ipec/publ/download/factsheets/fs_tea_0304.pdf

[28] International Labor Organization – IPEC. Hazardous Labor in Agriculture: Tea. https://www.ilo.org/public//english/standards/ipec/publ/download/factsheets/fs_tea_0304.pdf

[29] Sustainable Trade Initiative. Sector Overview: Tea. 2012. https://www.idhsustainabletrade.com/site/getfile.php?id=184.

[30] Sustainable Trade Initiative. Sector Overview: Tea. 2012. https://www.idhsustainabletrade.com/site/getfile.php?id=184.

Eldrig, Line. Fafo. Child Labor in the Tea Sector in Malawi. 2003. https://www.fafo.no/~fafo/media/com_netsukii/714.pdf

[31] Circar, Ranjan. Tea. Solidaridad Network. May 23, 2017. https://www.solidaridadnetwork.org/supply-chains/tea.

[32] Tea Association of the U.S.A. Inc. Tea Fact Sheet 2018-2019. https://www.teausa.com/14655/tea-fact-sheet

[33] Ethical Tea Partnership (ETP). An Overview of the Ethical Tea Partnership. September 2015. https://www.ethicalteapartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/ETP-Overview-Sept-2015.pdf

[34] Sherwell, Philip. “Clean water finally flows to transform lives of tea pickers in Bangladesh.” The Guardian. March 14, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/mar/14/clean-water-finally-flows-to-transform-lives-tea-pickers-bangladesh-surma-valley

[35] UNICEF Annual Report 2017. Rwanda. 2017. https://www.unicef.org/about/annualreport/files/Rwanda_2017_COAR.pdf

[36] Traidcraft Exchange. “Who picked my tea?” https://www.traidcraft.org.uk/tea-campaign