Soaring demand for West African cocoa fuels a seasonal, labor-intensive sector where low incomes and fragile supply chains drive trafficking risks.

Smallholder farms, typically under five acres and dependent on cocoa for survival, struggle with low yields, pests, and lack of access to credit, health care, and education. These pressures, combined with reliance on seasonal and hazardous manual labor, heighten risks of child labor, debt bondage, and exploitation of migrant workers.

Overview of cocoa production in Sub-Saharan Africa

Trade

The West African countries of Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, and Cameroon export nearly 70 percent of the world’s cocoa. Côte d’Ivoire alone accounts for 40 percent of global cocoa production.

[1]

In 2017, the top importers of cocoa beans from sub-Saharan Africa were the Netherlands, the United States, France, Belgium, and Germany.[2]

Europe consumes nearly 50 percent of the world’s chocolate, and the United States consumes approximately 25 percent.[3] The chocolate industry in the United States imports approximately USD 335 million in processed cocoa as well as USD 435 million in cocoa beans, which are then processed in the United States.

Global demand for cocoa is rising, but production has been constrained in West Africa for a range of reasons, including a labor shortage tied to an aging producer population, aging trees and general low productivity, agricultural diseases, and land shortages constraining farm expansion.

[4]

Features of production and supply chain

Most West African cocoa comes from small family farms under five acres in size, and in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, 90 percent of cocoa farmers are reliant on the crop for their livelihood. Cocoa farming families and communities face an increasing number of livelihood challenges, including low yields, pests, and lack of access to farming inputs and credit. Like other communities in rural sub-Saharan Africa, cocoa farming communities often lack access to health care and educational opportunities.

Cocoa production is labor intensive and seasonal. Cocoa producers must clear forest around their plantation, plant seedlings, weed their plantations, clear overgrown or older trees, prune trees, apply pesticides and fertilizers and harvest pods. Cocoa is relatively sensitive to weather changes, light/shade conditions, pests, and disease. In West Africa, the peak harvest season is roughly November – January, with an off-peak harvest in August and September. Cocoa pods grow on trees and are generally harvested by hand using machetes or hooks. The pods are cut open with machetes so the beans inside can be removed. The beans ferment for several days, and the pulp melts away before the beans are spread out to dry in the sun. After the beans are sorted and dried, they are stored in sacks before being picked up by collectors or transporters.

Producers may sell their beans themselves as individuals, or they may work through cooperatives, which can provide benefits such as loans and credit lines, improved access to social services, and bargaining power with buyers. Some cooperatives offer certification programs to participating producers. Cooperatives range from relatively unorganized operations serving fewer than 100 farmers, to large, highly organized operations serving thousands. Cooperatives may be contracted to larger traders. After processing, the beans are exported to the global market, where they are purchased by manufacturers.

The market in Ghana is uniquely regulated. COCOBOD, the government board, purchases beans from farmers via authorized traders who are required to pay a minimum price. These traders then sell to the government-run Cocoa Marketing Company, which manages exports.

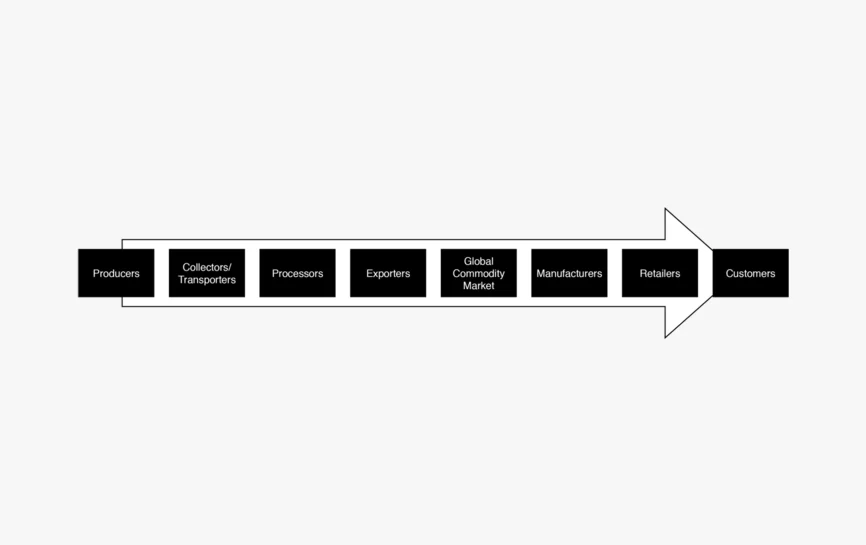

Example of cocoa supply chain model

The large number of intermediaries in cocoa supply chains can obscure the origins of beans while also decreasing the overall value accruing to farmers.[5]

Average incomes for cocoa producers are low, and producers contend with aging/unproductive trees, variable weather and climate change, limited access to credit and inputs, land insecurity, and price fluctuations.[6] Producers may have to take on debt to purchase inputs or arrange for transportation for their beans. Producers who need cash quickly or are unable to arrange transportation for their beans have limited marketing options, thus requiring them to accept lower prices for cocoa, which can contribute to cycles of debt and poverty. Producers who have lower incomes themselves are more likely to rely on vulnerable workers, including migrants and children.

Key documented trafficking in persons risk factors in cocoa production

According to the U.S. Department of State’s 2017 Trafficking in Persons Report, cocoa is listed as being produced with forced labor or forced child labor in Cameroon, Republic of the Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo.[7]

According to the U.S. Department of Labor’s List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, cocoa is produced with forced labor in Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria.[8]

Undesirable and hazardous work

Workers, particularly children, can be exposed to pesticides and are often injured by machetes used in harvesting.[9] They are vulnerable to musculoskeletal disorders, eye injuries, skin rashes, and coughing and often lack access to protective equipment.[10] Cocoa farms are often highly isolated, leaving workers, particularly migrant workers, without access to support or recourse when faced with undesirable or hazardous working conditions.[11]

Vulnerable workforce

[12]

Child labor

According to the U.S. Department of Labor’s List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, cocoa is produced with child labor in Cameroon, Ghana, Guinea, and Sierra Leone.[13]

Child labor is widespread in cocoa production. An estimated 1.8 million children in West Africa are involved in growing cocoa, 800,000 of whom are estimated to be in Côte d’Ivoire.[14] A 2015 report published by Tulane University compared the 2008-2009 cocoa harvest cycle to the 2013-2014 harvest cycle in terms of active child labor in both Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. The report found that child labor in Ghana decreased by six percent between the two harvest cycles, lowering from 930,000 children in 2008-2009 to 880,000 million children in 2013-2014.[15] The report found that in Côte d’Ivoire, child labor increased by 46 percent between the two harvest cycles, rising from 790,000 children in 2008-2009 to 1.15 million children in 2013-2014. It is important to note that this increase was likely due in part because cocoa production overall increased significantly.[16]

Gendered dynamics of production

Cocoa in West Africa is typically considered a “male crop,” but women contribute about half the labor on smallholder cocoa farms, particularly in plant care, as well as the fermenting and drying processes.[17] At the same time, women are less likely to benefit from cocoa earnings, or to participate in cooperatives or other producer organizations.[18] Men are nearly exclusively involved in marketing and price negotiation, limiting female producers’ economic power. In Côte d’Ivoire, Oxfam cite statistics from the African development bank that women make up more than half of the cocoa workforce but control less than a quarter of the earnings.[19]

Less than 25 percent of Fair Trade small producers in Africa – which includes many cocoa farmers – are women.[20]

Migrant labor

The cocoa sector in Côte d’Ivoire has long been associated with a migrant workforce, and there are significant diaspora communities originating from neighboring countries. Among heads of cocoa producing households interviewed by Tulane University in Côte d’Ivoire in 2014, 15 percent originated from Burkina Faso and 2.4 percent were from Mali. Of children interviewed in that study, two percent were not born in Côte d’Ivoire.[21]

In Côte d’Ivoire, trafficking has been documented among migrant workers – particularly teenage boys coming from the neighboring countries of Burkina Faso and Mali. Upon their arrival at the isolated cocoa farms, some workers were subjected to unsafe work and living conditions and not paid.[22]

[23]

Presence of labor intermediaries

Research has found that some migrant workers, including those subjected to indicators of forced labor as described above, were recruited by intermediaries.[24] In some cases, workers were required to pay back recruitment-related fees, which could equal the entire first year’s salary.[25] There have been anecdotal reports of similar recruitment systems in Nigeria, but significantly less research has been conducted there.[26]

Associated contextual factors contributing to trafficking in persons vulnerability

Association with environmental degradation

Between 1988 and 2007, cocoa cultivation in West Africa drove the deforestation of more than two million hectares of forest. Farmers clear forest because freshly deforested soils are more nutrient dense.[27] Ongoing climate change is shifting the zones with climates appropriate for cocoa cultivation, which also causes farmers to expand into previously forested areas.[28]