Trafficking Risk in Sub-Saharan African Supply Chains

Home / Explore by Commodity / Explore by Country / Understand Risk / Additional Resources / About the Project

Wood

Summary of Key Trafficking in Persons Risk Factors in Wood Production

✓ Vulnerable Workforce

Indigenous Populations

✓ Associated Contextual Factors Contributing to Trafficking in Persons Vulnerability

Association with State Corruption

Association with Environmental Degradation

Association with Large-scale Land Acquisition/Displacement

Overview of Wood Production in Sub-Saharan Africa

TRADE

The top exporters of wood products from sub-Saharan Africa in 2018 were Cameroon, Gabon, South Africa, Equatorial Guinea, and the Republic of the Congo.[1]

[2]

Other top exporters include Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone, Swaziland, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.[3]

The top importers of wood and wood products from sub-Saharan Africa were China, Belgium, India, Japan, and France. China is the most significant importer by far,[4] accounting for about 75 percent of all timber exports from Africa, with more than 60 percent of those exports coming from the Republic of the Congo, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, and Mozambique.[5] In Mozambique specifically, nearly 90 percent of timber goes to China, about half of which is logged illegally.[6] Previous analysis has noted Chinese circumvention of protocols intended to improve sector governance. For example, in 2011, Gabon banned export of unprocessed wood in an attempt to increase Gabon’s value share of the timber supply chain. However, after a brief drop off in exports to China, trade has mostly continued unabated.[7] In some cases, this circumvention of regulation may involve corruption, bribery, smuggling, and underreporting of trade.[8]

FEATURES OF PRODUCTION AND SUPPLY CHAIN

Africa has significant forest resources. In the Congo basin alone, roughly 200 million hectares are forested.[9] Forest products contribute about six percent of Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP) and more than half of GDP for West and Central Africa. Revenue comes primarily from high-value forest products such as mahogany, found in the Congo basin where the forest is densest.

Illegal logging and overharvesting in general is a significant issue, with over half of all forestry activities characterized as illegal in several African countries.[10] Illegal logging can take several forms: logging in conservation/environmentally protected areas, logging protected species of trees, or logging in excess of production limits. To complicate matters further, informal logging is widespread and represents an important subsistence activity for many local populations, but the legality of these activities varies depending on context.[11] Overall, Africa experiences deforestation at a rate of about four million hectares per year.[12]

Illegal logging also decreases tax revenue base for governments. An estimated 5.3 million USD is lost annually in Cameroon while 10.1 million USD is lost annually in Gabon.[13] Illegal logging also generates significant revenue for armed groups and organized crime.[14]

In addition to logging for exported woods, round wood is used predominantly as a fuel source for local populations. Most round wood production in Africa occurs in natural forests. South Africa is the exception, where round wood is produced on plantations.[15]

In general, wood product supply chains in sub-Saharan Africa are characterized by low value addition, with a low-overall level of processing that happens on the continent, although some national governments, like Cameroon, are making efforts to change this by controlling exports of unprocessed wood.[16]

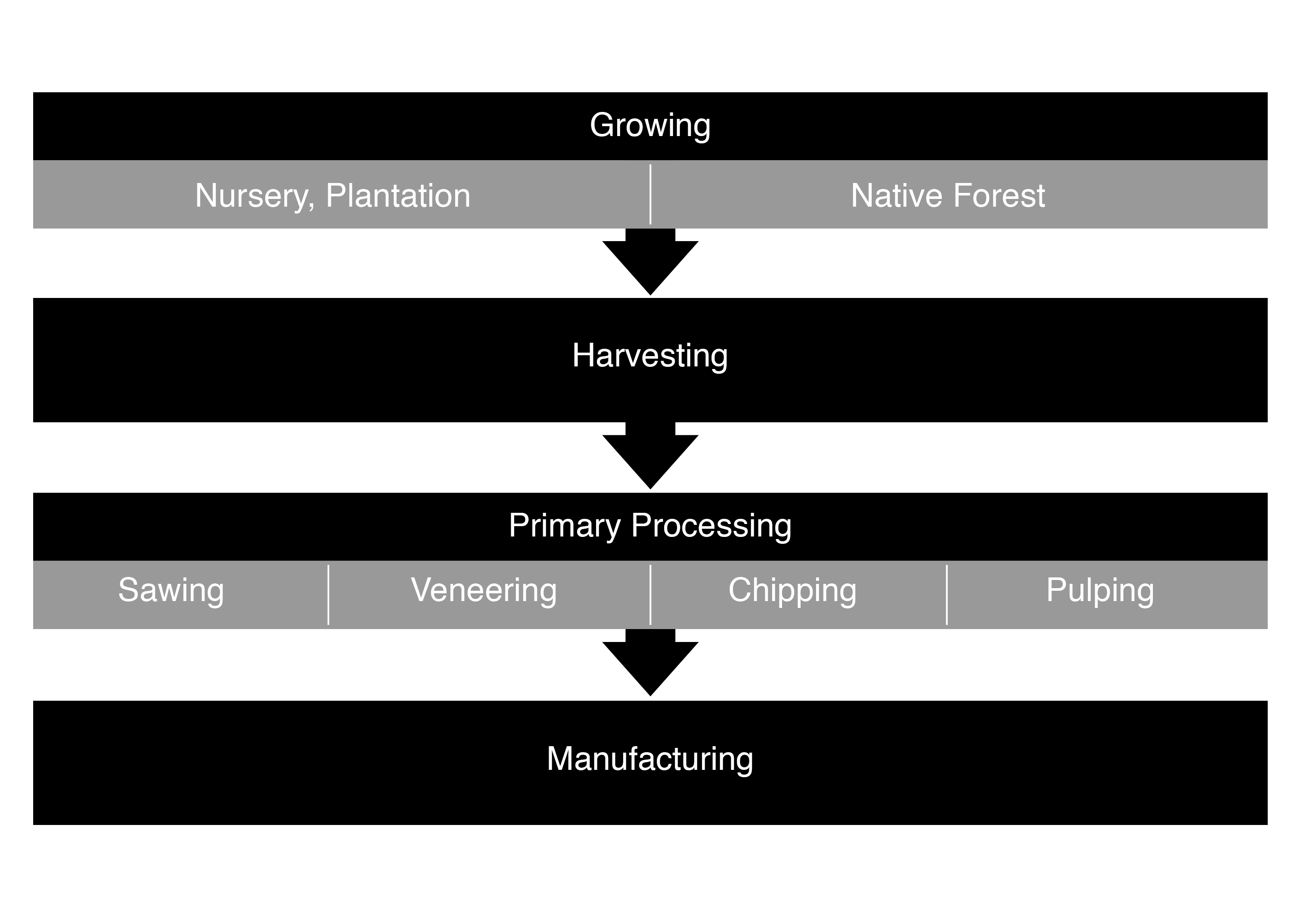

Example of Wood Supply Chain Model

[17]

Key Documented Trafficking in Persons Risk Factors in Wood Production

UNDESIRABLE AND HAZARDOUS WORK

Work in the forestry sector tends to be highly hazardous for workers under any conditions and is considered one of the most hazardous sectors.[19] These risks are increased in illegal operations that lack oversight. Heavy equipment, such as chainsaws, manual saws, and logging machines can cause serious injury. Further, many logging sites are inherently isolated, offering minimal or no options for medical care. The logs themselves are extremely heavy and may roll or fall around the logging site.[20] According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, forest sector workers globally are typically not adequately trained on health and safety.[21] Workers in densely forested tropical regions are at increased risk of diseases including those “transmitted by insects, such as malaria or dengue fever, intestinal worms or dysentery caused by contaminated food or water.”[22]

Due to the geographic location of many forestry sites, workers often stay at work camps in remote areas. The contractor responsible for the forestry operation often manages these temporary camps. The International Labor Organization has noted that the isolation of workers at these sites can be challenging in terms of labor standard enforcement.[23]

VULNERABLE WORKFORCE

Indigenous Populations

Indigenous peoples, such as the Baka pygmy populations, who live in forested areas may be displaced by concessions as described below. they are at risk for becoming a captive labor force on plantations or surrounding infrastructure. They may also be vulnerable to trafficking into other sectors as they lose access to livelihoods.[24]

ASSOCIATED CONTEXTUAL FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS VULNERABILITY

Associated Conflict

In several African countries, profits from illegal logging have been used by armed groups to fund conflicts. Typically, the military or other armed groups secure control over a forest concession area and use the proceeds as a source of revenue.[25] In some historical cases, governments in control during civil wars – such as during President Taylor’s regime in Liberia – have used logging as a means to finance arms. It should be noted however, that in other cases, previous research has noted that eruptions of civil conflicts can actually halt operation of preexisting logging concessions, which played out in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[26] Although the main linkage between logging and conflict has been the use of forest resources to fund conflict, a USAID report notes that “many African countries, because of their very lack of forest resources, appear far more vulnerable in the future to conflicts emerging from competition over forest resources.”[27]

In a 2015 report by Global Witness, exported wood from Central African Republic was described as “conflict timber.” This report documented how Chinese, French, and Lebanese companies made financial deals with Seleka rebel leaders for “protection services,” thus financing the group to procure additional arms. After 2014, the same companies made similar payments to another militia. By funding the conflict in Central African Republic, conflict timber has indirectly enabled the trafficking of child soldiers. Both parties to the conflict, have been documented to use forced child soldiers, and UNICEF has reported that nearly 10,000 child soldiers have been recruited since 2013.[28]

In countries with active or recent conflict histories, identification and protection of land rights become more challenging, particularly when claims are made by multiple stakeholders.[29] Given the overlap of forestry and conflict contexts in Africa, this is a compounding factor for displacement of indigenous peoples (see description of large-scale land acquisition below).

In many African countries, illegal logging or semi-legal logging has been facilitated by corrupt management of forest concessions. According to Global Witness and the Guardian, permits intended for local forestry companies are instead granted to large foreign industrial operations. In addition to the ability to log in these otherwise restricted areas, these companies operate broadly without government oversight. These practices were noted specifically in Ghana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, and Cameroon.[30] Global Witness’s reporting stated that “corruption is still the main threat to tropical rainforests, and is robbing communities and local people of their livelihoods.”[31] The role of government corruption in land grabs and displacement of local people is critical as governments administer or otherwise control the vast majority of forested areas in Africa.[32]

Land grabs in forested areas can be particularly detrimental to indigenous populations who rely on the forest for their livelihoods. The Baka pygmy populations in Central Africa, for example, have been displaced from traditional land by forestry concessions. These populations are marginalized by less access to citizenship documents and discrimination, which can act to prevent access to protective agencies and government programs. Given their close ties to ancestral land, they are at risk for becoming a captive labor force on plantations or surrounding infrastructure. They may also be vulnerable to trafficking into other sectors as they lose access to livelihoods.[33]

Large-scale commercial forestry plantations can also have environmental impact. According to the Oakland Institute, a foreign company in Tanzania is clearing over 7,000 hectares of natural fauna for pine and eucalyptus monoculture.[34] In Swaziland, commercial timber plantations use large amounts of water resources, which is particularly challenging in terms of Swaziland’s propensity for drought, and contributes to food insecurity for local people. Pollution from timber mills reportedly contributes to asthma and other illnesses for local populations.[35]

Any logging activity – regardless of legal status – requires heavy infrastructure investment, particularly around road construction.[36] A surge in logging operations, particularly in remote locations, may create an isolated population of workers vulnerable to trafficking. This increased infrastructure then opens access to forest previously inaccessible to any outside populations. For example, the logging sector has reportedly increased the bushmeat trade in Gabon as workers in the logging sector supplement their income with sales of bushmeat.[37] This increase in hunting in previously inaccessible areas may decrease biodiversity and contribute further to environmental degradation and loss of traditional livelihoods. In the Central African Republic, sales of bushmeat driven by the logging sector have increased so much that ape populations have been significantly threatened.[38] The increased contact with wildlife and bushmeat can encourage the spread of diseases like Ebola, creating negative impact on human health.[39]

[40]

[41]

Related Resources

Compliance Resources for Companies

Resources for Addressing Industry-Wide Issues and Root Causes

Explore Risk in Global Commodity Supply Chains

American Bar Association ROLI Case Study: Central African Republic Timber

Endnotes

[1] International Trade Centre. Trademap. www.trademap.org.

[2] International Trade Centre. Trademap. www.trademap.org.

[3] International Trade Centre. Trademap. www.trademap.org.

[4] Due to trade data aggregations, these estimates include some export value from some northern African countries.

[5] IIED. The dragon and the giraffe: China in African Forests. June 2015. https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/17302IIED.pdf.

[6] IIED. The dragon and the giraffe: China in African Forests. June 2015. https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/17302IIED.pdf.

[7] IIED. The dragon and the giraffe: China in African Forests. June 2015. https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/17302IIED.pdf.

[8] IIED. The dragon and the giraffe: China in African Forests. June 2015. https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/17302IIED.pdf.

[9] Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Global Forest Atlas. Congo Logging – Practice and Policy. https://globalforestatlas.yale.edu/congo/forests-and-logging/logging.

[10] Interpol. INTERPOL operations target illegal timber trade in Africa and the Americas. November 2015. https://www.interpol.int/News-and-media/News/2015/N2015-206.

Interpol; World Bank. Chainsaw Project: An Interpol perspective on law enforcement in illegal logging.

https://www.interpol.int/content/download/5354/44792/version/3/file/WorldBankChainsawIllegalLoggingReport[1].pdf.

[11] Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Study. Global Forest Atlas. Illegal Logging in the Congo Basin. https://globalforestatlas.yale.edu/congo/forests-and-logging/illegal-logging.

[12] Interpol; World Bank. Chainsaw Project: An Interpol perspective on law enforcement in illegal logging.

https://www.interpol.int/content/download/5354/44792/version/3/file/WorldBankChainsawIllegalLoggingReport[1].pdf.

[13] Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Study. Global Forest Atlas. Illegal Logging in the Congo Basin. https://globalforestatlas.yale.edu/congo/forests-and-logging/illegal-logging.

[14] Reid, Cait. Regulating Africa’s Timber Sector. This is Africa Online. https://www.thisisafricaonline.com/Analysis/Regulating-Africa-s-timber-sector?ct=true.

Interpol. INTERPOL operations target illegal timber trade in Africa and the Americas. November 2015. https://www.interpol.int/News-and-media/News/2015/N2015-206.

[15] Asumadu, K. Development of wood-based industries in Sub-Saharan Africa. August 2004. https://www.afforum.org/sites/default/files/English/English_126.pdf.

[16] Asumadu, K. Development of wood-based industries in Sub-Saharan Africa. August 2004. https://www.afforum.org/sites/default/files/English/English_126.pdf.

[17] Adapted from: Asumadu, K. Development of wood-based industries in Sub-Saharan Africa. August 2004. https://www.afforum.org/sites/default/files/English/English_126.pdf.

[18] Menne, Wally. Timberwatch Coalition. Timber Plantations in Swaziland: An investigation into the environmental and social impacts of large-scale timber plantations in Swaziland. December 2004. https://wrm.org.uy/oldsite/countries/Swaziland/Plantations.pdf.

[19] International Labour Organization. Safety and Health in Forestry Work. 1998. https://ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—safework/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_107793.pdf.

[20] International Labour Organization. Safety and Health in Forestry Work. 1998. https://ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—safework/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_107793.pdf.

[21] International Labour Organization. Safety and Health in Forestry Work. 1998. https://ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—safework/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_107793.pdf.

[22] International Labour Organization. Safety and Health in Forestry Work. 1998. https://ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—safework/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_107793.pdf.

[23] International Labour Organization. Safety and Health in Forestry Work. 1998. https://ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—safework/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_107793.pdf.

[24] Global Greengrants Fund. Cameroon’s Troubled Timber Industry: Discussion with Samuel Nnah Ndobe and Chris Allan. 2007. https://www.greengrants.org/pdf/cameroontimber.pdf.

Forests Monitor. Country Profiles. Central African Republic. https://www.forestsmonitor.org/en/reports/540539/549938

[25] Interpol; World Bank. Chainsaw Project: An Interpol perspective on law enforcement in illegal logging.

https://www.interpol.int/content/download/5354/44792/version/3/file/WorldBankChainsawIllegalLoggingReport[1].pdf.

[26] Thomson, Jamie and Ramzy Kanaan. USAID. Conflict Timber: Dimensions of the Problem in Africa and Asia. 2009.

https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnact462.pdf.

Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Global Forest Atlas. Congo Logging – Practice and Policy. https://globalforestatlas.yale.edu/congo/forests-and-logging/logging.

[27] Thomson, Jamie and Ramzy Kanaan. USAID. Conflict Timber: Dimensions of the Problem in Africa and Asia. 2009.

https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnact462.pdf.

[28] UNICEF. “Press Release: At least 65,000 children released from armed forces and groups over the last 10 years.” February 20, 2017. https://www.unicef.org/media/media_94892.html.

U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. Central African Republic. 2016. https://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/countries/2016/258741.htm.

[29] Interlaken Group. Respecting Land and Forest Rights: A Guide For Companies. 2015.

https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/31bcdf8049facb229159b3e54d141794/InterlakenGroupGuide_web_final.pdf?MOD=AJPERES.

[30] Vidal, Jon. “Illegal logging robbing people in Africa of livelihoods – Global Witness.” The Guardian. May 1, 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2013/may/01/illegal-logging-robbing-africa-livelihoods.

Global Witness. Logging in the Shadows: How Vested Interests Abuse Shadow Permits and Evade Sector Reforms. April 29, 2013. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/archive/logging-shadows-how-vested-interests-abuse-shadow-permits-evade-forest-sector-reforms/.

[31] Global Witness. Logging in the Shadows: How Vested Interests Abuse Shadow Permits and Evade Sector Reforms. April 29, 2013. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/archive/logging-shadows-how-vested-interests-abuse-shadow-permits-evade-forest-sector-reforms/.

[32] The Munden Project Limited. The Rights and Resources Institute. Tenure and Investment in Africa. 2016. https://rightsandresources.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Tenure-and-Investment-in-Africa_Trend-Analysis_TMP-Systems-RRI_Jan-2017.pdf.

[33] Global Greengrants Fund. Cameroon’s Troubled Timber Industry: Discussion with Samuel Nnah Ndobe and Chris Allan. 2007. https://www.greengrants.org/pdf/cameroontimber.pdf.

Forests Monitor. Country Profiles. Central African Republic. https://www.forestsmonitor.org/en/reports/540539/549938

[34] Oakland Institute. Investigation Reveals that Bad Energy and Development Policies Contribute to Famine and Conflict in Africa. 2011. https://www.oaklandinstitute.org/sites/oaklandinstitute.org/files/Oakland%20Institute%20Land%20Grab%20Release%20EMBARGOED.pdf.

[35] Menne, Wally. Timberwatch Coalition. Timber Plantations in Swaziland: An investigation into the environmental and social impacts of large-scale timber plantations in Swaziland. December 2004. https://wrm.org.uy/oldsite/countries/Swaziland/Plantations.pdf.

[36] Butler, Rhett. “Deforestation in the Congo Basin.” Mongabay News. January 23, 2016. https://rainforests.mongabay.com/congo/deforestation.html#.VZ6tC_lViko.

[37] World Resources Institute. A First Look at Logging in Gabon. https://www.wri.org/sites/default/files/pdf/gfw_gabon.pdf

[38] Asher, Claire. “Illegal bushmeat trade threatens human health and great apes.” Mongabay News. April 6, 2017. https://news.mongabay.com/2017/04/illegal-bushmeat-trade-threatens-human-health-and-great-apes/.

[39] Asher, Claire. “Illegal bushmeat trade threatens human health and great apes.” Mongabay News. April 6, 2017. https://news.mongabay.com/2017/04/illegal-bushmeat-trade-threatens-human-health-and-great-apes/.

[40] Transparency International. 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index. 2018. https://www.transparency.org/cpi2014.

[41] World Economic Forum. The Global Competitiveness Report 2018. 2019. https://reports.weforum.org/global-competitiveness-report-2018/competitiveness-rankings/#series=GCI4.A.01.06.

Trafficking Risk in Sub-Saharan African Supply Chains

Home / Explore by Commodity / Explore by Country / Understand Risk / Additional Resources / About the Project