Commodity Atlas

Gold

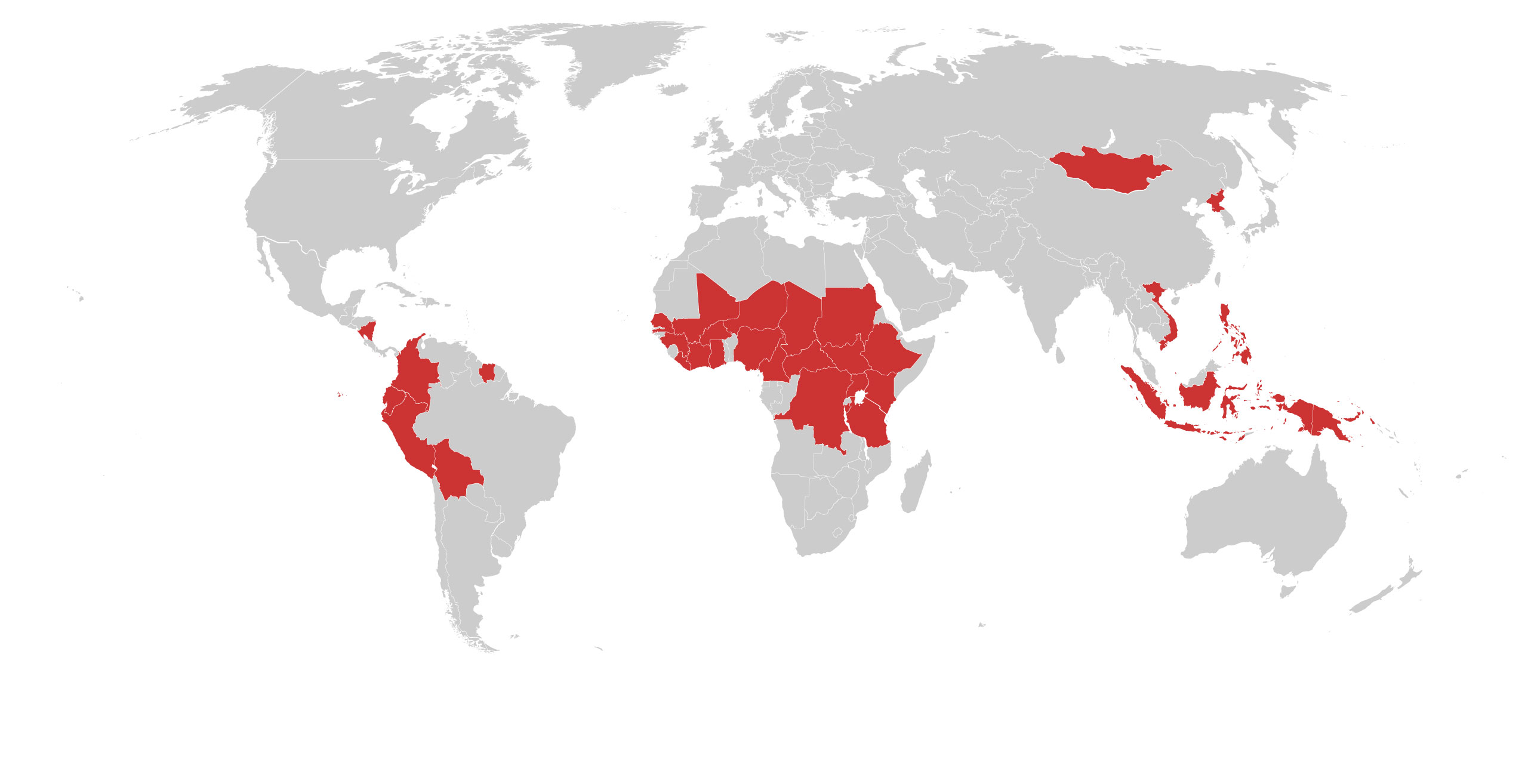

Countries Where Gold is Reportedly Produced with Forced Labor and/or Child Labor

| Gold is reportedly produced with forced labor (FL) and/or child labor (CL) in the following countries: |

|

|

|

Where is gold reportedly produced with trafficking and/or child labor?

The U.S. Department of Labor’s List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor indicates that gold is produced with child labor Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Indonesia, Mali, Mongolia, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, Philippines, Senegal, Sudan, Suriname, Tanzania, Uganda, and with forced labor in North Korea.[2b] The list states that both forced labor and child labor are present within the gold sectors of Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Peru.[3]

The 2018 U.S. Department of State Trafficking in Persons Report lists Colombia and the Philippines as Tier 1 countries and Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cote D’Ivoire, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, Peru, Tanzania, Uganda and Vietnam as Tier 2 countries. Central African Republic, Chad, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Mongolia, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sudan and Suriname are listed as Tier 2 Watch List countries. Bolivia, Burundi, DRC, Papua New Guinea and North Korea are listed as Tier 3 countries.[4]

Gold production and global supply chains:

The majority of the word’s gold – an estimated 75 percent in 2009 – is produced by large, multinational companies using advanced technology to extract gold in large-scale mines.[39] The remaining 25 percent is produced by artisanal mines.[40]

Gold is mined either through hard-rock or alluvial mining. In hard-rock mining, minerals and metals are extracted from rock, which can be done in large open-pit mines or in tunnels that are dug into rock faces. In alluvial mining, minerals and metals are extracted from water. This can be done through panning in rivers; sluicing, in which water is combined with materials (such as sand and dirt) and is channeled into boxes that sift and separate the minerals and metals from the material; and dredging, in which minerals and metal-laced sediment are sucked up from sediment in bodies of water.[41]

After the gold is mined, it must be separated from the material that bears it. In hard-rock mining, the rock is often ground into dust. The gold can either be separated using gravity concentration or chemical processes. Both mercury and cyanide are used and these chemicals must then be burnt off.[42] In artisanal and small-scale mining, mercury is used, and this dangerous process may take place in or around miners’ homes.[43]

Gold generally passes through several layers of consolidators, intermediaries, and exporters (some of whom may actually be illegal smugglers) before it enters into the processing level.[44] Once gold reaches refineries in countries including the United States and Switzerland, it becomes even more difficult to identify the origin of the gold, as gold from all over the world may be mixed and processed together. Refineries sell gold to banks, jewelry companies, and electronic producers around the world.[45]

Gold mined from countries embroiled in conflict is smuggled at high rates; Gold smuggling allows gold mined from sites controlled by armed groups to enter legitimate supply chain. It also encourages illegal gold mining activities in general and decreases government revenues.[46] For example, Uganda, which has refining capability, is thought to be a major regional receiver of gold smuggled from Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[47] The United Arab Emirates (UAE) receives a significant portion of gold smuggled from Africa. Ten percent of the UAE’s gold imports come from the ICGRL.[48] There are large discrepancies between reported exports of gold from ICGRL countries and the UAE’s imports of ICGRL gold.[49] The UAE has especially strong ties with the Sudanese gold market. Although exact data is unavailable, it is estimated that the UAE is a top importer of gold smuggled from the Central African Republic and West Africa.[50] From 2011 to 2014 the UAE’s imports of Malian gold surpassed Mali’s total reported production every year.[51]

Verité research has found that literally tons of illegally mined Latin American gold are purchased and used by central banks and major international jewelry and electronics producers, which are the main consumers of gold. A Verité analysis of Dodd-Frank Act compliance found that approximately 90 percent (64 out of the 72 Fortune 500 companies that filed conflict minerals disclosures in 2015) purchased gold from refineries with a pattern of sourcing illegally mined gold from Latin America.[52] A 2016 report by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime found direct links between some of the biggest exporters of illegally mined gold in both Peru and Colombia, and U.S.-based refineries that source gold to major electronics and jewelry brands, as well as links to the U.S. Federal Mint.[53]

How does trafficking and/or labor in

gold production affect me?

Jewelry accounts for the majority of all gold use. Globally, about 90 million carats of rough diamonds and 1,600 tons of gold are mined for jewelry every year, generating over USD 300 billion in revenue.[54] Due to its high conductivity, gold is also used in electronics such as cell phones and laptops. Small amounts of gold are also used in dentistry and medicine. In 2019, the World Gold Council estimated that there are 190,040 tons of gold in above ground stocks, with approximately 48 percent of the world’s gold in 90,718 tons of jewelry. Approximately 21 percent of the world’s gold was held by private investment, which held about 40,035 tons, and approximately 17 percent was held by federal reserves in 32,500 tons of gold.[55] As of 2019, the U.S. Geological Survey estimates that current underground reserves hold 54,000 tons of gold.[56]

In addition to using a large amount of gold in its banking sector, Switzerland is a global clearinghouse for gold, with much of the gold it imports eventually making its way into gold bullion, jewelry, watches, and electronics that end up in the hands of consumers in countries around the world. Up to 96 percent of the world’s gold may go to Switzerland at one point or another.[57]

Gold and the environment:

In addition to being linked to forced labor, gold production is highly destructive environmentally. Cyanide and mercury are used to separate gold particles, and smelting produces 13 percent of all sulfur dioxide annually.[58] The chemicals used in gold production pollute water and surrounding land and affect human health. For example, in Peru, high levels of mercury have been found in Lake Titicaca, much of which comes from the processing of gold in La Rinconada, the highest city in the world,[59] and in the Madre de Dios region, the Amazon Conservation Association (ACA) estimates that 30 to 40 tons of mercury are dumped annually. This causes more than half of the commonly eaten fish to contain unsafe amounts of mercury, leading 78 percent of residents to have unsafe levels of mercury in their blood.[60] In Zimbabwe, women living near gold mining areas where mercury is used were found to have extremely high levels of mercury in their breast milk, putting their nursing children at risk.[61]

Acidic water, which is highly toxic, can drain from mining sites, contaminating local water sources. Acidic water can also leach other metals from rocks, such as cadmium, arsenic, lead and iron into water. These can make water unpotable.[62]

Additionally, gold production is linked with deforestation. In the Madre de Dios region alone, 370,000 acres of rainforest have been lost to gold mining, and there is no indication that the deforestation will cease.[63] In the Sahel Region in West Africa, gold mining is contributing to drastic deforestation and desertification, as trees are cut down to line mine shafts.[64]

When local populations are displaced or lose access to their traditional livelihoods due to gold mining, they may become more vulnerable to exploitation in gold mining or other sectors.

LEARN MORE

What does trafficking and/or child labor in

gold production look like?

Trafficking risk in illegal gold mining is linked with the presence of criminal groups and violence. Ongoing violence contributes to an environment of lawlessness and corruption, creating a population of workers that is fearful and desperate for work. The mere presence of armed groups in an area can restrict workers’ freedom of movement, which in turn increases reliance on employers and reduces workers’ ability to seek outside help in addressing abuses at their workplaces, especially if workers are far from home. Governments also cannot carry out monitoring of labor conditions or law enforcement in violent areas. The work involved in illegal gold mining is dirty, dangerous, and difficult, making it unattractive to all but the most desperate people. Victims of displacement, minorities, and individuals who lack identity documents often work in mines due to a lack of alternative employment options. Moreover, the environmental damage and displacement caused by illegal mining itself produce more vulnerable people who may have no choice but to participate in illegal mining to survive.[5]

The high value and ease with which gold can be smuggled and sold into formal supply chains makes it an attractive form of income for armed groups. Armed groups may use profits from gold mining to fund their operations – which may involve other forms of trafficking such as sex trafficking and child soldiers. In some cases, these groups are perpetrators of trafficking. In Peru and Colombia, illegal gold mines are often controlled by criminal groups, and the revenue generated from this activity has surpassed the revenue generated by cocaine trafficking in the world’s top two cocaine producers.[6] In CAR, the Seleka and militia groups extract “taxes” from artisanal miners in areas they control, which are used to fund the conflict.[7] In other cases, these groups outright control illegal mines and the workers in them.[8] Similarly, in the DRC, armed groups control or benefit financially from several types of mines, including gold mines.[9] Miners may be forced to work under threat of violence or may be required to pay a “tax” to armed groups. Profits from gold mining, as well as mining of minerals including cassiterite, columbite-tantalite and wolframite, fund the ongoing conflict in the country.[10] The U.N. has noted that illicit gold mining and smuggling is funding the ongoing conflict in Sudan,[11] which is associated with the use of child soldiers.[12] According to the U.S. Department of State, children have been used as combatants by the Sudanese military and there have been reports that the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Sudanese Rapid Response Forces recruited boys under 18 years old.[13] A U.N. expert council also reported that child combatants took part in tribal clashes for control of gold mines.[14]

Discoveries of gold in a region can lead to “rushes” of migration, particularly in areas where people have lost other livelihood options. In the Kedougou region of Senegal, villagers who cannot support their families through agriculture or have lost their land to logging have turned to gold mining out of necessity.[15] This rush has precipitated a large-scale migration of migrants from neighboring countries such as Mali, Guinea, Gambia, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Togo, and Nigeria.[16]

The isolated nature of many mining regions as well as the “rush” nature of production can create highly vulnerable populations in mining camps and towns. Incidents of sex trafficking and document retention have been noted in growing mining towns in Kedougou.[17] Verité has noted a high risk of both labor and sex trafficking in and around illegal mining operations in Peru.[18] International organizations are becoming increasingly aware of forced labor risk for Venezuelan migrant workers in Peru, who are recruited to work in the illegal gold mining sector.[19] Research from Free the Slaves has noted that, in Ghana, “Traditional social systems of protection are currently weakened or rarely in use in and around galamsey[20] gold mining communities (presumably in part because these are more transient communities).”[21] Human Rights Watch has noted that girls working on or near mining sites in Ghana face “sexual harassment, sexual exploitation and rape.”[22] Child prostitution and child sex trafficking has been noted anecdotally around mining camps in Mali,[23] Tanzania[24] and Mozambique.[25]

Child labor is also strongly associated with artisanal and illegal mining in a wide variety of countries including Mali,[26] Ghana,[27] Burkina Faso,[28] and the Philippines.[29] An ILO expert has stated that, “the more remote and more informal a small-scale mining activity, the more likely children are to be involved.”[30] In many cases, children and juveniles are among the migrant workers in mining, travelling either with their families or independently.[31] In general, child laborers in gold mining include both children working voluntarily, as a means of supporting themselves or their families, and children who have been trafficked. The ILO has noted that in general, the wages children earn in mining are less than those earned by adults.[32]

Although not a trafficking risk in itself, artisanal gold mining is highly hazardous and presents serious health hazards to all workers, especially children. The mining shafts in which workers, including teenage boys, often work are usually unstable and children can suffer severe injuries or death from falls and collapsed mine shafts.[33] The dust from pulverizing stone can lead to lung damage. Younger children often dig out the pits with sharp tools and carry heavy bags of ore, both of which can lead to musculoskeletal injuries.[34]

In artisanal gold mining, powdered ore is mixed with mercury to create an amalgam that workers burn to evaporate the mercury and collect the gold. Women and children often perform this task at mining camps. This process is detrimental to workers’ health, as exposure to mercury can cause developmental and neurological problems, especially among children.[35] For women, mercury exposure has been identified as a leading cause of birth defects.[36] Mercury may be ingested (accidentally during work or through contaminated water), absorbed through the skin (when it is handled with bare hands or miners swim in mercury contaminated water), or inhaled (when the mercury is burnt off pieces of gold). This can result in inflammation of vital organs, the inability to urinate, shock, and death. It can also result in skin lesions, irritation to the lungs, difficulty breathing, and permanent damage to the nervous system.[37] Verité research in Peru indicates that in some formal processing plants, workers are also exposed to cyanide with minimal personal protective equipment (PPE) and many workers are exposed to mercury with little or no PPE in illegal gold mining.[38]

Examples of what governments, corporations,

and others are doing:

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is undertaking a high-level initiative to develop a due diligence policy for coltan, tungsten, tin and gold mining in conflict and high-risk scenarios, particularly the DRC. Forced labor is one of the indicators of “intolerable abuses” in this due diligence guide.[65]

In March 2010, the Fairtrade Labeling Organization (FLO) and the Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM) launched a Fairmined Standard for Gold and Associated Precious Metals. “Fairmined” gold certified under the standard must meet social, environmental, labor and economic requirements in artisanal mining communities. As of 2018, eight mines in four countries were Fairmined certified and an additional 20 mining organizations were in the process of becoming certified.[66] Fairmined certified. Fairmined is working across Latin America, Asia, and Africa to improve mining practices. The annual production of Fairmined certified gold is roughly 500 kilograms per year.[67]

The Responsible Jewelry Council (RJC) is a membership organization which aims to improve conditions in gold and diamond supply chains. In 2009, the RJC initiated a certification program for its members’ gold and diamond supply chains requiring obligatory third-party auditing.[68] In 2012, RJC launched a Chain-of-Custody (CoC) certification. RJC has also partnered with the Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM) to “improve social, environmental and labor practices…enhance relationships between large-scale mining and artisanal and small-scale mining and increase market access for precious metals from responsible artisanal and small-scale mining.”[69] In partnership with ARM, in 2016 RJC piloted a combined Fairmined and CoC audit of metals refiner Metalor Technologies SA “with the objective of reducing audit burden, without compromising the quality and rigour of the audit process.” [70]

No Dirty Gold, a campaign from the NGO Earthworks, seeks to promote environmental and social standards in gold mining. As of 2017, more than 115 companies had signed on to the No Dirty Gold’s “12 Golden Rules” for sourcing, including eight out of the top ten jewelry retailers, with Target being the most recent addition.[71] The Madison Dialogue is another industry-focused organization which does not offer a certification program, but instead seeks to build engagement in the gold and diamond supply chains.[72]

In response to the hazards mercury poses to the environment and human health, whether used in gold mining or elsewhere, the UN Environmental Program (UNEP) drafted a convention on mercury, called the Minamata Convention. The convention was agreed to in January 2013, was ratified in the U.S. in June 2013, and has been signed by 128 countries and ratified by 70 countries worldwide as of 2018.[73] Signatories of the convention agree to measures limiting and controlling the mining, manufacture, storage, and trade of mercury; this includes a ban on the creation of new mercury mines and an agreement to cease operations of already operating mercury mines within 15 years.[74]

In 2019, the Peruvian Government declared a state of emergency in Madre de Dios, sending 1,500 police and military officers to the region for a police operation to destroy illegal gold mining machinery.[75]

Endnotes

[1b] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[2b] U.S. Department of Labor. 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. 2018. https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ilab/ListofGoods.pdf

[3] U.S. Department of Labor. 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. 2018. https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ilab/ListofGoods.pdf

[4] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[5] Verité. The Nexus of Illegal Gold Mining and Human Trafficking in Global Supply Chains. 2016. https://verite.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Verite-Report-Illegal_Gold_Mining-2.pdf

[6] Verité. The Nexus of Illegal Gold Mining and Human Trafficking in Global Supply Chains. 2016. https://verite.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Verite-Report-Illegal_Gold_Mining-2.pdf

[7] Gridneff, Ilya. “Blood Gold Flows Illegally From Central African Republic.” Bloomberg. March 8, 2015. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-03-08/blood-gold-exports-pour-illegally-from-central-african-republic

[8] Flynn, Daniel. “Gold, diamonds feed Central African religious violence.” Reuters. July 29, 2014. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-centralafrica-resources-insight-idUSKBN0FY0MN20140729

Hoije, Katrina. “Rebeles Retain Control of Rich Mine in Central African Republic.” VOA News. November 21, 2013. https://www.voanews.com/a/rebels-retain-control-mine-central-african-republic/2530046.html

[9] Human Rights Watch. “The Hidden Cost of Jewelry: Human Rights in Supply Chains and the Responsibility of Jewelry Companies.” February 2018. https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/02/08/hidden-cost-jewelry/human-rights-supply-chains-and-responsibility-jewelry

[10] Free the Slaves. The Congo Report: Slavery in Conflict Minerals. June 2011. https://www.freetheslaves.net/document.doc?id=243

Global Witness. Faced With A Gun, What Can You Do? 2009. https://www.globalwitness.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/englishsummary.pdf

Bariyo, Nicholas; Freeman, Francesca; Pleven, Liam. “Inside Congo’s link in the Gold Chain.” The Wall Street Journal. April 14, 2013. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323820304578410273270663086

[11] Charbonneau, Louis. Nichols, Michelle. Reuters. “U.N. experts report cluster bombs, gold smuggling in Darfur.” April 5, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-sudan-darfur-un-idUSKCN0X22SL

[12] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2016. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258876.pdf.

[13] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2016. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258876.pdf.

[14] United Nations Security Council. “Report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Sudan.” March 6, 2017. https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2017/191&Lang=E&Area=UNDOC.

[15] International Organization for Migration. “Gold rush in Kédougou, Senegal: Protecting migrants and local communities” Global Eye on Human Trafficking. 2012. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/globaleyeissue11_29feb2012.pdf

[16] International Organization for Migration. “Gold rush in Kédougou, Senegal: Protecting migrants and local communities” Global Eye on Human Trafficking. 2012. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/globaleyeissue11_29feb2012.pdf

[17] Guilbert, Kieran. “Sex for the soil: Senegal’s gold rush fuels human trafficking from Nigeria.” Thomson Reuters Foundation. March 30, 2017. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-senegal-trafficking-sexwork-idUSKBN1711A4

[18] Verité. Risk Analysis of Indicators of Forced labor and Human Trafficking in Illegal Gold Mining in Peru. 2013. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/IndicatorsofForcedLaborinGoldMininginPeru.pdf

[19] Dupraz-Dobias, Paula. “Worries grow as more Venezuelans look to Peru.” The New Humanitarian. January 11, 2019. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2019/01/11/Peru-Venezuela-worries-grow-refugees-migrants-crisis.

[20] Illegal or informal mining sites

[21] Free the Slaves. “Child Slavery, Child Labor and Exploitation of Children in Mining Communities Obuasi, Ghana.” 2013. https://www.freetheslaves.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Summary-of-Findings-Child-Rights-in-Mining-Ghana-January-2013.pdf

[22] Human Rights Watch. “Precious Metal, Cheap Labor. Child Labor and Corporate Responsibility in Ghana’s Artisanal Gold Mines.” 2015 https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/06/10/precious-metal-cheap-labor/child-labor-and-corporate-responsibility-ghanas

[23] Human Rights Watch (HRW). A Poisonous Mix: Child Labor, Mercury, and Artisanal Gold Mining In Mali. December 6, 2011. https://www.hrw.org/report/2011/12/06/poisonous-mix/child-labor-mercury-and-artisanal-gold-mining-mali.

[24] York, Geoffrey. The Globe and Mail. “Claims of sexual abuse in Tanzania blow to Barrick Gold.” May 30, 2011. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/claims-of-sexual-abuses-in-tanzania-blow-to-barrick-gold/article598557/.

[25] Thielke, Thilo. Der Spiegel. “Digging for Survival: The Gold Slaves of Mozambique.” March 24, 2011. https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/digging-for-survival-the-gold-slaves-of-mozambique-a-543047.html.

[26] Human Rights Watch. “Mali: Artisanal Mines Produce Gold With Child Labor Hazardous Work, Mercury Poisoning, and Disease.” 2011. https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/12/06/mali-artisanal-mines-produce-gold-child-labor

[27] Human Rights Watch. “Precious Metal, Cheap Labor. Child Labor and Corporate Responsibility in Ghana’s Artisanal Gold Mines.” 2015 https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/06/10/precious-metal-cheap-labor/child-labor-and-corporate-responsibility-ghanas

[28] Price, Larry C. “One Million Children Labor in Africa’s Goldmines. PBS Newshour. July 10, 2013. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/world-july-dec13-burkinafaso_07-10/

[29] Human Rights Watch. ““What … if Something Went Wrong?” Hazardous Child Labor in Small-Scale Gold Mining in the Philippines.” September 29, 2015. https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/09/29/what-if-something-went-wrong/hazardous-child-labor-small-scale-gold-mining

[30] International Labor Organization. “The burden of gold Child labour in small-scale mines and quarries.” August 1, 2005. https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/world-of-work-magazine/articles/WCMS_081364/lang–en/index.htm

[31] Thorsen, Dorte. Children Working in Mines and Quarries – Evidence from West and Central Africa. UNICEF. April 2012. https://www.unicef.org/wcaro/english/Briefing_paper_No_4_-_children_working_in_mines_and_quarries.pdf

[32] International Labor Organization. “The burden of gold Child labour in small-scale mines and quarries.” August 1, 2005. https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/world-of-work-magazine/articles/WCMS_081364/lang–en/index.htm

[33] Internal Verité research.

[34] Human Rights Watch (HRW). Toxic Toil: Child Labor and Mercury Exposure in Tanzania’s Small-Scale Gold Mines.” August 2013. https://www.hrw.org/node/118031/

[35] Human Rights Watch (HRW). Toxic Toil: Child Labor and Mercury Exposure in Tanzania’s Small-Scale Gold Mines.” August 2013. https://www.hrw.org/node/118031/

[36] Gonzalez, David. “Mercury exposure and risk among women of childbearing age in Madre de Dios, Peru.” Tropical Resources 34, 16–24. 2015.

No Dirty Gold. Where Gold is Mined. https://www.nodirtygold.org/stdnt_where.cfm

[37] International Labor Organization (ILO). Peligros, Riesgos y Daños a La Salud de Los Niños y Niñas que Trabajan en la Minería Artesanal. Organización Internacional del Trabajo. 2005. https://white.oit.org.pe/ipec/documentos/cartilla_riesgos_min.pdf

[38] Verité. Risk Analysis of Indicators of Forced labor and Human Trafficking in Illegal Gold Mining in Peru. 2013. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/IndicatorsofForcedLaborinGoldMininginPeru.pdf

[39] Verité. Risk Analysis of Indicators of Forced labor and Human Trafficking in Illegal Gold Mining in Peru. 2013. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/IndicatorsofForcedLaborinGoldMininginPeru.pdf

Larmer, Brook. “The Real Price of Gold.” National Geographic. January 2009. https://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2009/01/gold/larmer-text

[40] Larmer, Brook. “The Real Price of Gold.” National Geographic. January 2009. https://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2009/01/gold/larmer-text

[41] Ethical Gold Fund. Mining Process. https://www.ethicalgoldfund.com/#!mining-process/c248p

[42] Verité. Risk Analysis of Indicators of Forced labor and Human Trafficking in Illegal Gold Mining in Peru. 2013. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/IndicatorsofForcedLaborinGoldMininginPeru.pdf

[43] UN Environmental Program (UNEP). A Practical Guide: Reducing Mercury Use in Artisanal and Small Scale Gold Mining. July 2012. https://www.unep.org/chemicalsandwaste/Portals/9/Mercury/Documents/ASGM/Techdoc/UNEP%20Tech%20Doc%20APRIL%202012_120608b_web.pdf

[44] Verité. The Nexus of Illegal Gold Mining and Human Trafficking in Global Supply Chains. 2016. https://verite.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Verite-Report-Illegal_Gold_Mining-2.pdf

[45] Verité. Risk Analysis of Indicators of Forced labor and Human Trafficking in Illegal Gold Mining in Peru. 2013. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/IndicatorsofForcedLaborinGoldMininginPeru.pdf

[46] Shoko, Janet. The Africa Report. “Zimbabwe losing millions to gold smuggling.” February 25, 2014. https://www.theafricareport.com/Southern-Africa/zimbabwe-losing-millions-to-gold-smuggling.html.

[47] Human Rights Watch (HRW). Uganda: Undermined. June 2017. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/oil-gas-and-mining/uganda-undermined/.

[48] Martin, Alan. Taylor, Bernard. Partnership Africa Canada. All that Glitters is Not Gold: Dubai, Congo and the Illicit Trade of Conflict Minerals. May 2014. https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/all-glitters-not-gold-dubai-congo-and-illicit-trade-conflict-minerals

[49] Martin, Alan. Taylor, Bernard. Partnership Africa Canada. All that Glitters is Not Gold: Dubai, Congo and the Illicit Trade of Conflict Minerals. May 2014. https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/all-glitters-not-gold-dubai-congo-and-illicit-trade-conflict-minerals.

[50] Matthysen, Ken; Clarkson, Iain. Gold and Diamonds in the Central African Republic. February 2013. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Gold%20and%20diamonds%20in%20the%20Central%20African%20Republic.pdf.

[51] Martin, Alan. Helbig de Balzac, Hélène. Partnership Africa Canada. The West African El Dorado: Mapping the Illicit Trade of Gold in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and Burkina Faso. January 2017. https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/west-african-el-dorado-mapping-illicit-trade-gold-c%C3%B4te-d%E2%80%99ivoire-mali-and-burkina.

[52] Verité. The Nexus of Illegal Gold Mining and Human Trafficking in Global Supply Chains: Lessons from Latin America. July 2016. https://verite.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Verite-Report-Illegal_Gold_Mining-2.pdf

[53] The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. Organized Crime and Illegally Mined Gold in Latin America. April 2016. https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/TGIATOC-OC-and-Illegally-Mined-Gold-in-Latin-America-Report-1718-digital.pdf

[54] Human Rights Watch. “The Hidden Cost of Jewelry.” February 8, 2019. https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/02/08/hidden-cost-jewelry/human-rights-supply-chains-and-responsibility-jewelry.

[55] World Gold Council. How Much Gold has been mined? March 7, 2019. https://www.gold.org/about-gold/gold-supply/gold-mining/how-much-gold.

[56] U.S. Geological Survey. 2019 Gold Commodity Report. https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/gold/

[57] Mariani, Daniel. “Switzerland: the World’s Gold Hub.” Swissinfo.ch. October 12, 2012. https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/business/Switzerland:_the_world_s_gold_hub.html?cid=33706126

[58] No Dirty Gold. Where Gold is Mined. https://www.nodirtygold.org/stdnt_where.cfm

[59] Verité. Risk Analysis of Indicators of Forced labor and Human Trafficking in Illegal Gold Mining in Peru. 2013. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/IndicatorsofForcedLaborinGoldMininginPeru.pdf

[60] Amazon Conservation Association. Fact Sheet: Illegal Gold Mining in Madre de Dios, Peru. https://www.amazonconservation.org/pdf/gold_mining_fact_sheet.pdf

Collyns, Dan. “Peru’s Gold Rush Sparks Fear of Ecological Disaster.” BBC. December 20, 2009. https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8411408.stm

[61] Mambondiyani, Andrew. “Zimbabwe’s desperate gold rush poisons children with mercury” Reuters. July 13, 2015. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-zimbabwe-gold-mercury-idUSKCN0PN26H20150713

[62] Brilliant Earth. Gold Mining and the Environment. https://www.brilliantearth.com/gold-mining-environment/

[63] Amazon Conservation Association. Fact Sheet: Illegal Gold Mining in Madre de Dios, Peru. https://www.amazonconservation.org/pdf/gold_mining_fact_sheet.pdf

[64] The Guardian. “Battling the Effects of Gold Mining in Burkina Faso.” September 5, 2011. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/gallery/2011/sep/05/burkina-faso-gold-in-pictures#/?picture=378427673&index=10

[65] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Draft Due Diligence Guidelines for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas. 2010. https://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/13/18/46068574.pdf

[66] Human Rights Watch. “The Hidden Cost of Jewelry: Human Rights in Supply Chains and the Responsibility of Jewelry Companies.” February 2018. https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/02/08/hidden-cost-jewelry/human-rights-supply-chains-and-responsibility-jewelry

[67] Alliance for Responsible Mining. Fairmined Gold. https://www.communitymining.org/en/1-fairmined-gold

[68] Responsible Jewellery Council. Gold and the Jewelry Supply Chain. May 18, 2010. https://www.responsiblejewellery.com/downloads/RJC_18_May_Philip_Olden.pdf

[69] Responsible Jewellery Council. Artisanal and Small-scale Mining. https://www.responsiblejewellery.com/artisanal-and-small-scale-mining/

[70] Responsible Jewellery Council. Artisanal and Small-scale Mining. https://www.responsiblejewellery.com/artisanal-and-small-scale-mining/

[71] No Dirty Gold. Where Gold is Mined. https://www.nodirtygold.org/stdnt_where.cfm

[72] Fair Jewelry Action. The Madison Dialogue: A Cross-Sector Initiative. https://www.fairjewelry.org/the-madison-dialogue-a-cross-sector-initiative/

[73] Minamata Convention on Mercury. List of Signatories and Future Parties. https://www.mercuryconvention.org/Countries/Parties/tabid/3428/language/en-US/Default.aspx.

[74] UN Environmental Program (UNEP). Minimata Convention on Mercury: Text and Annexes. October 2013. https://www.mercuryconvention.org/Portals/11/documents/Booklets/Minamata%20Convention%20on%20Mercury_booklet_English.pdf

[75] Taj, Mitra. “Peru launches crackdown on illegal gold mining in Amazon.” Reuters. February 19, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-peru-illegal-mining/peru-launches-crackdown-on-illegal-gold-mining-in-amazon-idUSKCN1Q82U6.