Commodity Atlas

Fish

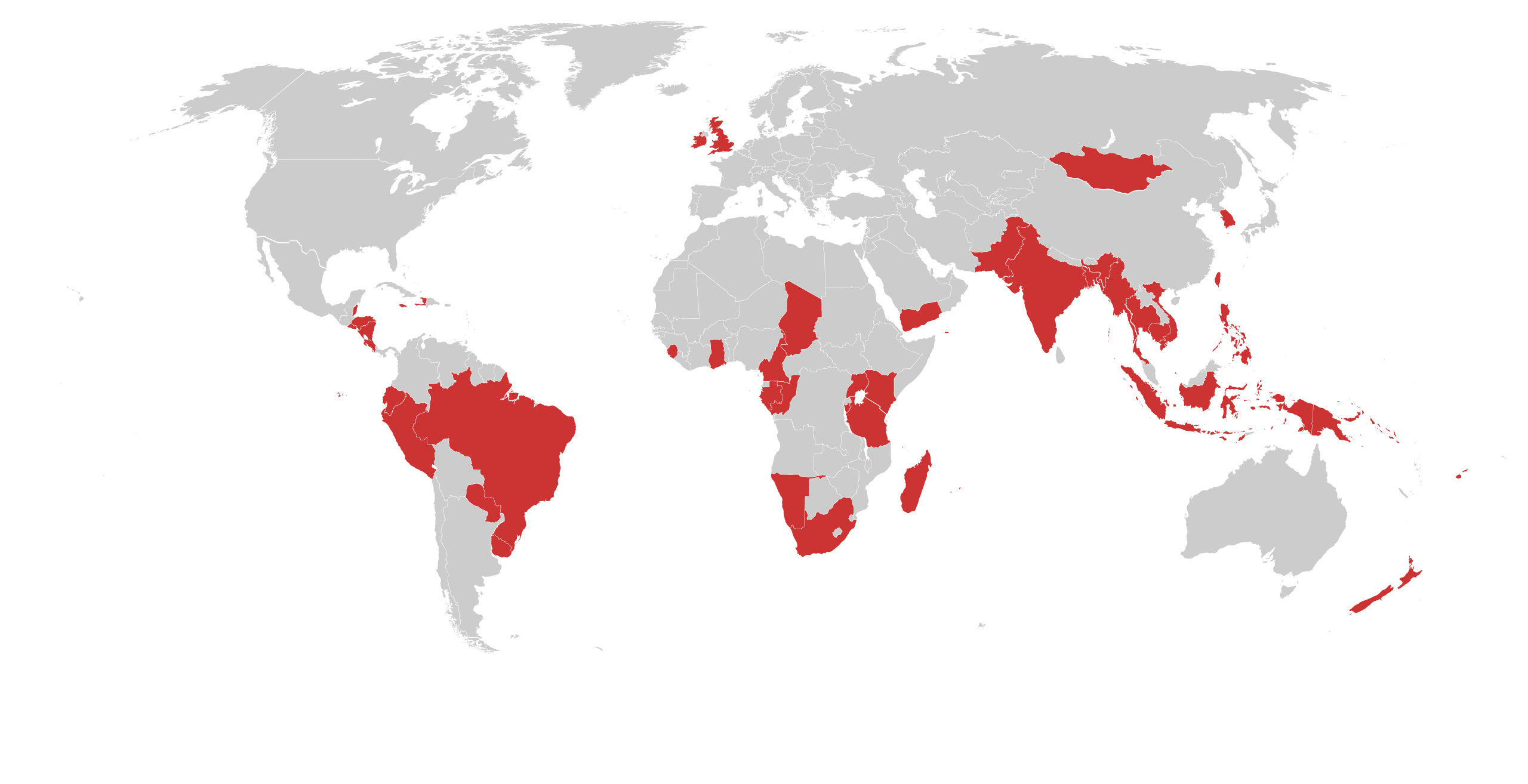

| Fish is reportedly caught/harvested/processed with forced labor (FL) and/or child labor (CL) in the following countries: | |

|

|

Where are fish reportedly caught, harvested,

and processed with trafficking and/or

child labor?

The U.S. Department of Labor’s 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor notes that fish/seafood products are produced with forced labor and child labor in Bangladesh, Ghana, and Indonesia. The list notes forced labor in the production of fish products in Thailand. Child labor is noted in Brazil, Cambodia, El Salvador, Kenya, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Tanzania, Uganda, Vietnam and Yemen.[2b]

The U.S. Department of State 2018 Trafficking in Persons Report lists Republic of Korea, New Zealand, Philippines, Taiwan, and United Kingdom as Tier 1 countries. Brazil, Cambodia, Cameroon, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Ghana, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Jamaica, Kenya, Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Micronesia, Namibia, Pakistan, Palau, Paraguay, Peru, Singapore, Solomon Islands, Tanzania, Thailand, Uganda, Uruguay, and Vietnam are listed as Tier 2 countries. Bangladesh, Chad, Fiji, Haiti, Madagascar, Mongolia, Nicaragua, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, and South Africa are listed as Tier 2 Watch List countries. Belize, Burma, Burundi, Comoros, Republic of Congo, Gabon, and Papua New Guinea are listed as Tier 3 countries. Yemen is listed as a special case.[3]

Gathering region-specific data on forced labor in ocean fishing is difficult because many fishing vessels travel in international waters and have crews from multiple countries. In many instances, the country of vessel ownership, the port state, the vessel’s flag state, the coastal state, and the nationality of the workers on board will all be different. For example, the U.S. Department of State reported in 2018 that workers from South and East Asian countries boarded fishing vessels that were primarily China and Taiwan-flagged from ports located in Fiji and worked on those vessels in Fiji’s territorial waters.[4]

Fish supply chain

The seafood sector is characterized by complex supply chains. In fact, “chain” is a slightly misleading term because the layers, including multiple levels of middlemen, can be so intricate and opaque as to more closely resemble a web. Fish and shellfish are harvested in open waters or raised via aquaculture in ponds, tanks, or bounded coastal waters. Some wild-caught fish may be transported from the catching vessel by transshipment vessel to market. After harvest, fish are sold via auction, broker, or market system and then packed and transported to processing facilities or wholesalers. Fish may be sold as fillets, or other fresh products, or processed into consumer goods such as canned, frozen, or smoked products. Some fish may pass through multiple levels of processing, while others, such as certain kinds of shellfish, are transported live. Wholesalers receive processed products and more minimally processed fresh fish from both foreign and domestic sources. The wholesalers then distribute the products to retailers and restaurants, where they are purchased by consumers.

How do trafficking and/or child labor in

fishing affect me?

Fish is the most highly traded food commodity, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization; in 2016, global per capita fish consumption exceeded 20 kilograms per person, an all-time high.[29]

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reports that “for two thirds of the world’s population, including most of the world’s poor, fish provides at least 40 percent of protein consumption.”[30] Americans consumed about 11.5 pounds of seafood in 2015, of which about 90 percent was imported.[31] About half of fish imported into the U.S. is wild-caught. In addition, a significant amount of fish ariving in the U.S. is exported to foreign countries for processing, and then re-imported to the U.S. for consumption.[32]

Examples of what governments, corporations,

and others are doing:

After reports of human trafficking in the seafood sector, Thailand rolled out wide-ranging activities to combat trafficking, although NGOs note that implementation has been inconsistent.[33] The Thai Ministry of Social Development and Human Security (MSDHS) included activities to specifically combat human trafficking in the fishing sector in the 2013 National Action Plan to Prevent and Suppress Human Trafficking (NAP). In 2015, the government strengthened the legal framework governing the fishing sector, including legislation around working conditions, distant water fishing and vessel monitoring (VMS) requirements.[34] The government also created databases to collect and share information on human trafficking as well as fishing vessels, licenses, and crews.[35] In 2018, the Royal Thai Police established the Thailand Anti-Trafficking in Persons Task Force to help coordinate law enforcement efforts.[36] However, the U.S. Department of State reported that “trafficking in the fishing industry remains a significant concern.”[37]

On January 30, 2019 Thailand ratified the International Labour Organization’s Work in Fishing Convention, 2007 (No. 188) which will come into force on January 30, 2020. The convention outlines binding requirements concerning fishing vessel-based work; requirements cover occupational safety and health, medical care and rest periods, and labor rights such as written work agreements and social security protection.[38]

In July 2018, The Ministry of Fishers and Aquaculture Development (MOFAD) in Ghana approved a national strategy to help eradicate child labor and trafficking in Ghanaian fishing communities, which was developed in collaboration between MOFAD and the USAID Sustainable Fisheries Management Project.[39]

The European Union is currently funding a project, implemented by the ILO, the “Ship to Shore Rights” Project (“Combatting Unacceptable Forms of Work in the Thai Fishing and Seafood Industry”) which works towards “the prevention and reduction of unacceptable forms of work in the Thai fishing and seafood processing sectors.” Partners in the project include the Thai Government, employers’ organizations, workers’ organizations, and buyers. The project’s four key objectives are to strengthen policy and regulatory frameworks governing the seafood sector; enhance government capacity to identify and take action against forced labor and labor rights violations; improve seafood and fishing industry compliance with the ILO’s Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work; and support workers and victims of labor abuses.[40]

The International Labor Rights Forum created the Independent Monitoring at Sea (IM@Sea) project in 2016, which was designed to address vulnerabilities commonly faced by migrant workers employed in the Thai fishing sector; the project sought to enable workers to maintain connectivity while at sea, to improve assessments for labor risks, and to develop worker-driven grievance mechanisms. The IM@Sea project developed a set of data collection tools, based on a system already in place to electronically document and trace fish caught by fishing vessels, which allowed vessel monitoring, electronic catch reporting, electronic video monitoring, and the specialized survey application to be bundled together.[41]

In 2017, the Thai Union Group collaborated with Greenpeace and the International Transport Workers Federation to create and enforce a code of conduct for fishing vessels that supply fish stock to them in order to combat the abuses onboard vessels widely reported in the media; the group has also implemented an ethical migrant recruitment policy program to reduce the debt migrant workers gain when traveling to Thailand for work.[42] Also in 2017, Thai Union, in cooperation with Thailand’s Department of Fisheries, Inmarsat, Xsense, Mars Pet Care, and USAID Oceans, piloted a program to test the degree to which Catch Documentation and Traceability (CDT) technology could be used to improve crew communication while at sea. Overall, the pilot found that the technology, in addition to improving traceability, “improved crew morale and retention on board the vessels.”[43] In February 2018, Thai Union and Nestlé launched a demonstration fishing that displays examples of “good living and working conditions.”[44]

What does trafficking and/or child labor

in fishing look like?

Verité and the ILO have identified several contributing factors to forced labor in fishing. Employment in the fishing sector is highly dependent on the local context, the size of the vessel, and the type of fishing undertaken. Fishers employed on larger boats may have relatively formal employment agreements with the captain of the vessel or fleet ownership, but contracts are rare. Workers may be recruited through formal or informal labor recruiters, to whom they owe debt for their job placement. Often workers recruited through brokers will have no advanced knowledge of their actual employer. On small boats, employment relationships are predominantly casual and may be based on traditional relationships such as patronage, leading workers to be highly dependent on their boss. Further complicating the employment relationship, payment on both large and small fishing vessels often follows the traditional “share” system in which each worker’s pay is based on an allotment of net proceeds from the catch after output expenses (food, fuel, etc.) are deducted. Under this system, workers are considered “partners” in the fishing venture rather than employees and are therefore denied legal protections available to other classes of workers.[5] In general, the International Labor Rights Forum has noted that labor abuses related to fishing are driven by and enable illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing.[6]

The “share” system also means that crew members share financial risk with owners. If a voyage does not clear a profit, workers may not be compensated, leaving them vulnerable to debt. Fishers may also have their pay docked for items consumed on board including cigarettes, alcohol, medicine, and in some cases, food. These items are often deducted at highly inflated rates. In some cases, a workers’ family may also take loans from the boat ownership while the fisher is at sea. These loans are also deducted from the fisher’s pay at high interest. Fishers paid under some version of the “share” system often lack access to information about how a voyage’s profit is calculated and therefore, cannot assess whether calculations of their earnings are fair. For example, workers interviewed by Verité in the Philippines tuna sector noted that they are barred from observing the catch being weighed; this leaves them reliant on the vessel owner’s word and leads to the perception that they are being cheated.[7]

Rates of abuse are high on fishing vessels. Regardless of formal employment relationships, crews are generally overseen by a captain or boss. The captain or boss has a high financial stake in a profitable voyage, which can incentivize abusive management practices including actual or threatened physical abuse (hitting, violence with weapons, denial of rest), verbal abuse (yelling, threats), and other forms of intimidation.[8] In extreme cases, crew members have reported witnessing bosses murder crew members onboard vessels.[9] Workers aboard fishing vessels are inherently isolated, particularly on larger vessels that can stay at sea for extended periods of time, leaving workers with limited means of escape or avenues to report abuse. Fishing operations take place across national and maritime boundaries, leaving workers under the legal jurisdiction of the country in which the vessel is flagged. In cases where the vessel is using a flag of convenience, workers have severely limited legal protection.[10]

For example, recent media reporting and NGO publications from 2014 to 2017 have documented severe abuses of migrant workers in Thailand’s seafood sector, including (but not limited to) beatings, torture, killings, dangerous work and regular injury/infection, deplorable living conditions, wage theft, excessive overtime with shifts lasting up to 20 hours, debt bondage, and lack of work contracts and grievance mechanisms.[11] In March 2018, the ILO Ship to Shore Rights Project released a report exploring progress since this media coverage noting fewer incidents of physical violence, fewer workers under 18, an increase in fishers who have written contracts, and higher average monthly wages before deductions for some fishers since; however, the report also indicated that fishers continued to be paid less than minimum wage, a persistent gender pay gap, that about one quarter of fishers had pay withheld by a vessel owner, and that some fishers did not have access to their identity documents.[12] Vessels in the Thai fishing sector may remain at sea for long periods of time due to decreasing fish-stocks; larger vessels may stay out for up to a year while smaller vessels transship caught fish. When vessels remain at sea they largely operate outside law enforcement oversight.[13] The unappealing nature of these long voyages compounds the labor shortage in the Thai fishing sector and increases its dependence on often vulnerable migrant workers.[14] Verité research on migrant workers in the Thai fishing sector found workers in debt-bondage after deceptive recruitment. Several workers interviewed reported that they had been “sold” to a boat captain by a labor broker. Workers reportedly could not leave without facing financial penalties, and Vessel-based workers reported that they had restricted freedom of movement, even while in port.[15]

A 2015 investigation by the Guardian found that fishers from Ghana, the Philippines, Egypt, and India were working under conditions of forced labor in Ireland. Workers interviewed reported being recruited by labor agencies, and some reported debt arising from illegal recruitment fees. Workers reported abusive conditions, including lower than legal minimum wage. Because they were undocumented, they were confined to the vessel even while it was in port as they feared being deported.[16] Despite the development of a permit scheme specifically for vessel owners to hire non-European Economic Area workers following the 2015 media coverage, The Guardian reported in 2018 that labor rights violations, and in some cases trafficking, of foreign workers in the Irish fishing sector have continued. The violations include wages well below the minimum wage and extremely long hours resulting in industrial injury. The permit scheme also ties migrant workers to a single employer, further increasing their vulnerability.[17]

The ILO identifies fishing as a highly hazardous sector due to rough weather, exposure to sun and salt water without protective clothing, slippery/moving work surfaces, regular use of sharp tools, inadequate sleeping quarters, inadequate sanitation, and lack of fresh food and water. In addition, the work itself is highly labor intensive. When setting nets or hauling a catch, workers may be required to work around the clock for days without breaks. Workers report high degrees of fatigue, which further increases the risk of accidents.[18]

Labor rights abuses and hazardous working conditions can also occur at the level of fish processing onboard large vessels or in port cities. Workers who pack fish on ice often report frost bite symptoms in the fingers. Few workers are provided adequate health and safety gear. When injuries and illness do occur, medical care is rarely provided.[19] Burmese and Cambodian workers have been trafficked into working in fish processing plants in Thailand through the same mechanisms that boat workers are recruited.[20] In the Philippines tuna canning sector, where there has been a shift towards a highly “casual” labor system, Verité found indicators of exploitive labor among the primarily female workers at a facility. For example, workers are hired through manpower cooperatives or recruiters and therefore do not have a direct relationship with the canning facilities. Several workers reported wage deductions and forced overtime.[21]

Child labor is present throughout the fishing sector. In informal fishing, children dive for fish because they are believed to have stronger lungs than adults. These children may dive without any protective gear, putting them at high risk for injury or death. Due to the highly hazardous nature of the fishing work in general, it is often considered a worst form of child labor.[22] Verité research found child labor in fish drying workshops in Indonesia. Girls as young as ten work alongside their mothers and are responsible for sorting, boiling, salt processing, and drying the fish. Because this work is conducted overnight, many of the girls drop out of school due to exhaustion.[23]

Children, some as young as four, have been found in conditions of forced labor connected to fishing taking place on and around Lake Volta in Ghana; in some instances, this is a result of human trafficking.[24] The typical trafficking mechanism in this region is a contractual agreement between the children’s parents and a recruiter, who is often a fisher, usually for a multiple year period; parents are given an advance payment or promised payment at the end of the contract. In many cases, both the parents and children lack awareness of the actual conditions of work prior to the child’s arrival at the worksite.[25] While some recruiters promise job training and access to education, abusive work conditions and lack of interim payment may mean that children enter a situation of human trafficking.[26] Children are reportedly controlled by physical violence, threats and withholding of adequate food, as well as intense social pressure.[27] Recent studies have found that girls are recruited as well as boys. In certain communities, this practice is reportedly widespread with up to 50 percent of children from a village leaving to work on Lake Volta.[28]

LEARN MORE

- Watch a series of videos by the EJF on flags of convenience and pirate fishing.

- Read a Verité report on trafficking in the Philippines.

- Read a Verité report on human trafficking for forced labor indicators in fish supply chains in Indonesia.

- Read a Verité report on human trafficking for forced labor indicators in tuna supply chains in the Philippines.

- Read a Human Rights Watch report on abuses in the Thai fishing sector.

- Read an International Transport Workers Federation report on labor abuses in fishing and transport.

Endnotes

Note that this includes workers in forced labor or found to be in conditions of forced labor in recent years both in vessels leaving or docking in a country’s ports or active in a country’s territorial waters.

[2b] U.S. Department of Labor. 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor of Forced Labor. https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ilab/ListofGoods.pdf

[3] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

Note that this includes workers in forced labor or found to be in conditions of forced labor in recent years both in vessels leaving or docking in a country’s ports or active in a country’s territorial waters.

[4] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018.

[5] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Fish in Indonesia: Platform (Jermal) Fishing, Small-Boat Anchovy Fishing, and Blast Fishing. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Indonesian%20Fishing%20Sector__9.16.pdf

Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Tuna in the Philippines. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Philippines%20Tuna%20Sector__9.16.pdf

International Labor Organization (ILO). Caught at Sea: Forced Labour and Trafficking in Fisheries. 2013. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—declaration/documents/publication/wcms_214472.pdf

[6] “Taking Stock: Labor Exploitation, Illegal Fishing, and Brand Responsibility in the Seafood Industry.” International Labor Rights Forum. May 2018. https://laborrights.org/sites/default/files/publications/Taking%20Stock%20final.pdf

[7] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Fish in Indonesia: Platform (Jermal) Fishing, Small-Boat Anchovy Fishing, and Blast Fishing. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Indonesian%20Fishing%20Sector__9.16.pdf

Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Tuna in the Philippines. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Philippines%20Tuna%20Sector__9.16.pdf

[8] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Fish in Indonesia: Platform (Jermal) Fishing, Small-Boat Anchovy Fishing, and Blast Fishing. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Indonesian%20Fishing%20Sector__9.16.pdf

Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Tuna in the Philippines. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Philippines%20Tuna%20Sector__9.16.pdf

International Labor Organization (ILO). Caught at Sea: Forced Labour and Trafficking in Fisheries. 2013. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—declaration/documents/publication/wcms_214472.pdf

[9] International Labor Organization (ILO). Caught at Sea: Forced Labour and Trafficking in Fisheries. 2013. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—declaration/documents/publication/wcms_214472.pdf

[10] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Fish in Indonesia: Platform (Jermal) Fishing, Small-Boat Anchovy Fishing, and Blast Fishing. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Indonesian%20Fishing%20Sector__9.16.pdf

Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Tuna in the Philippines. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Philippines%20Tuna%20Sector__9.16.pdf

International Labor Organization (ILO). Caught at Sea: Forced Labour and Trafficking in Fisheries. 2013. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—declaration/documents/publication/wcms_214472.pdf

[11] “Taking Stock: Labor Exploitation, Illegal Fishing, and Brand Responsibility in the Seafood Industry.” International Labor Rights Forum. May 2018.

https://laborrights.org/sites/default/files/publications/Taking%20Stock%20final.pdf

Environmental Justice Foundation. Slavery at Sea: The Continued Plight of Trafficked Migrants in Thailand’s Fishing Industry. March 4, 2014. https://ejfoundation.org/node/1062

Hodal, Kate; Kelly, Chris. The Guardian. “Trafficked into slavery on Thai trawlers to catch food for prawns.” June 10, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/jun/10/-sp-migrant-workers-new-life-enslaved-thai-fishing.McDowell, Robin; Mendoza, Martha; Mason, Margie. Associated Press. “Are Slaves Catching the Fish You Buy?” March 25, 2015. https://bigstory.ap.org/article/b9e0fc7155014ba78e07f1a022d90389/ap-investigation-are-slaves-catching-fish-you-buy

Stoakes, Emanuel; Kelly, Chris; Kelly, Annie. The Guardian. “Revealed: how the Thai fishing industry trafficks, imprisons and enslaves.” July 20, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/jul/20/thai-fishing-industry-implicated-enslavement-deaths-rohingya.

Urbina, Ian. New York Times. “Sea Slaves: The Human Misery That Feeds Pets and Livestock.” July 27, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/27/world/outlaw-ocean-thailand-fishing-sea-slaves-pets.html?_r=1.

[12] ILO Ship to Shore Rights Project, “Measuring progress towards decent work in Thai fishing and seafood industry,” March 7, 2018, www.ilo.org/asia/media-centre/news/WCMS_619724/lang–en/index.htm.

[13] Verité. Recruitment Practices and Migrant Labor Conditions in Nestlé’s Thai Shrimp Supply Chain. 2016. https://verite.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/NestleReport-ThaiShrimp_prepared-by-Verite.pdf

[14] Undercurrent News. “Thai Fishing Industry in Labor Shortage.” January 22, 2015.

[15] Verité. Recruitment Practices and Migrant Labor Conditions in Nestlé’s Thai Shrimp Supply Chain. 2016. https://verite.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/NestleReport-ThaiShrimp_prepared-by-Verite.pdf

[16] Lawrence, Felicity; McSweeney, Ella; Kelly, Annie; Heywood, Matt; Susman, Dan; Kelly, Chris; Domokos, John. “Revealed: trafficked migrant workers abused in Irish fishing industry.” The Guardian. November 2, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/nov/02/revealed-trafficked-migrant-workers-abused-in-irish-fishing-industry

[17] Lawrence, Felicity and Ella McSweeney. “Permit scheme facilitating slavery on Irish fishing boats, says union.” The Guardian. May 18, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/may/18/permit-scheme-facilitating-slavery-on-irish-fishing-boats-says-union

[18] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Fish in Indonesia: Platform (Jermal) Fishing, Small-Boat Anchovy Fishing, and Blast Fishing. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Indonesian%20Fishing%20Sector__9.16.pdf

Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Tuna in the Philippines. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Philippines%20Tuna%20Sector__9.16.pdf

International Labor Organization (ILO). Caught at Sea: Forced Labour and Trafficking in Fisheries. 2013. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—declaration/documents/publication/wcms_214472.pdf

[19] M F Jeebhay et al. “World at work: Fish processing wokers.” Occupational and environmental medicine 61(5):471-4.. June 2004. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8612348_World_at_work_fish_processing_workers

[20] Mirror Foundation. 2011. Trafficking and Forced Labour of Thai Males in Deep-sea Fishing (Bangkok). As cited in: International Labor Organization (ILO). Employment Practices and Working Conditions in Thailand’s Fishing Sector. 2013. www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_220596.pdf

Environmental Justice Foundation. “Sold to The Sea: Human Trafficking in Thailand’s Fishing Industry.” 2013. https://ejfoundation.org/resources/downloads/Sold_to_the_Sea_report_lo-res-v2.compressed-2.compressed.pdf

[21] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Tuna in the Philippines. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Philippines%20Tuna%20Sector__9.16.pdf

[22] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Fish in Indonesia: Platform (Jermal) Fishing, Small-Boat Anchovy Fishing, and Blast Fishing. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Indonesian%20Fishing%20Sector__9.16.pdf

Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Tuna in the Philippines. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Philippines%20Tuna%20Sector__9.16.pdf

International Labor Organization (ILO). Caught at Sea: Forced Labour and Trafficking in Fisheries. 2013. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—declaration/documents/publication/wcms_214472.pdf

[23] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Fish in Indonesia: Platform (Jermal) Fishing, Small-Boat Anchovy Fishing, and Blast Fishing. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Indonesian%20Fishing%20Sector__9.16.pdf

[24] U.S. Department of Labor. 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor of Forced Labor. https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ilab/ListofGoods.pdf

U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[25] International Justice Mission. Child Trafficking into Forced Labor on Lake Volta, Ghana. 2016. https://www.ijm.org/sites/default/files/resources/ijm-ghana-report.pdf

[26] International Justice Mission. Child Trafficking into Forced Labor on Lake Volta, Ghana. 2016. https://www.ijm.org/sites/default/files/resources/ijm-ghana-report.pdf

[27] International Justice Mission. Child Trafficking into Forced Labor on Lake Volta, Ghana. 2016. https://www.ijm.org/sites/default/files/resources/ijm-ghana-report.pdf

[28] International Justice Mission. Child Trafficking into Forced Labor on Lake Volta, Ghana. 2016. https://www.ijm.org/sites/default/files/resources/ijm-ghana-report.pdf

[29] https://laborrights.org/sites/default/files/publications/Taking%20Stock%20final.pdf

[30] UN Conference on Trade and Development. Commodity Atlas: Fishery Products. 2004. https://www.unctad.org/en/docs/ditccom20041ch9_en.pdf

[31] White, Cliff. “American Seafood Consumption up in 2015.” SeafoodSource. October 27, 2016. https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/american-seafood-consumption-up-in-2015-landing-volumes-even

[32] Fishwatch. Sustainable Seafood: The Global Picture. https://www.fishwatch.gov/sustainable-seafood/the-global-picture

[33] Humanity United. Assessing Government and Business Responses to the Thai Seafood Crisis. 2016. https://humanityunited.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/FF_HU_Assessing-Reponse_FINAL_US-copy.pdf

[34] Humanity United. Assessing Government and Business Responses to the Thai Seafood Crisis. 2016. https://humanityunited.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/FF_HU_Assessing-Reponse_FINAL_US-copy.pdf

[35] Humanity United. Assessing Government and Business Responses to the Thai Seafood Crisis. 2016. https://humanityunited.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/FF_HU_Assessing-Reponse_FINAL_US-copy.pdf

[36] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/countries/2018/282764.htm

[37] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/countries/2018/282764.htm

[38] “Thailand ratifies Work in Fishing Convention.” The ILO. January 30, 2019. https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_666581/lang–en/index.htm

[39] U.S. Embassy in Ghana. “U.S. Government Supports Ghana to Develop Anti-Child Labor and Trafficking Strategy for the Fisheries Sector.” October 24, 2018. https://gh.usembassy.gov/u-s-government-supports-ghana-to-develop-anti-child-labor-and-trafficking-strategy-for-the-fisheries-sector/

Free The Slaves, “Trafficking’s Footprint: Two-Phase Baseline Study of Child Trafficking in 34 Communities in 6 Districts in Ghana.” April 2018. https://www.freetheslaves.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Traffickings-Footprint-in-Ghana-April-2018.pdf

[40] “About Us.” Ship to Shore Rights. https://shiptoshorerights.org/about/

[41] “Taking Stock: Labor Exploitation, Illegal Fishing, and Brand Responsibility in the Seafood Industry.” International Labor Rights Forum. May 2018. https://laborrights.org/sites/default/files/publications/Taking%20Stock%20final.pdf

[42] Janssen, Peter. “Thai junta takes the stench off troubled fisheries industry.” Asiatimes.com. December 17, 2018. https://www.asiatimes.com/2018/12/article/thai-junta-takes-the-stench-off-troubled-fisheries-industry/

[43] USAID. Thai Union eCDT and Crew Communications Pilot: Assessment Report. March 2018. https://www.seafdec-oceanspartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/USAID-Oceans_Thai-Union-eCDT-and-Crew-Communications-Pilot-Assessment_March-2018.pdf

[44] Neslté. “Inauguration of demo boat, a milestone in Thai fishing industry.” February 28, 2018. https://www.nestle.com/media/news/inauguration-demo-boat-thai-fishing-industry-thailand