Commodity Atlas

Citrus

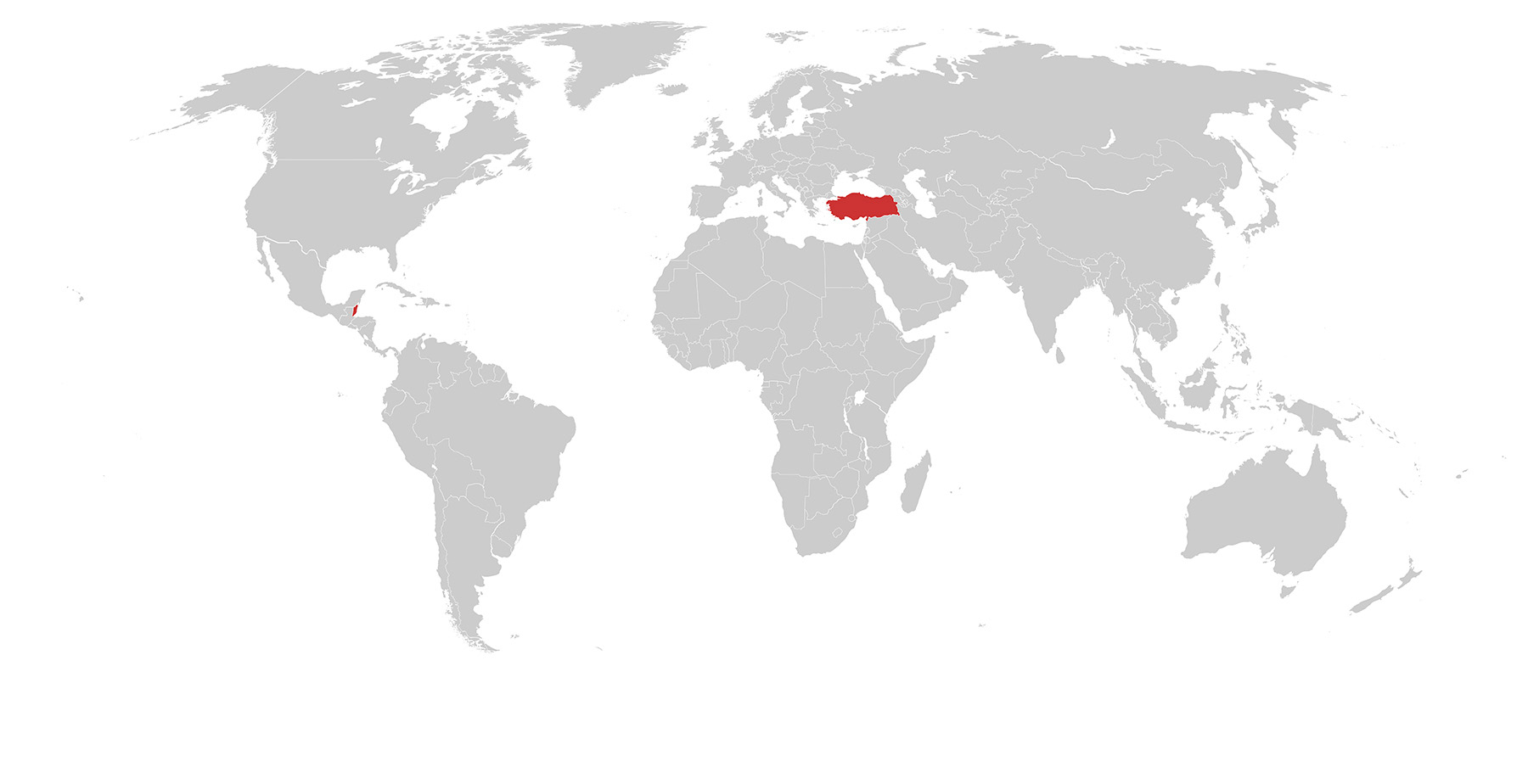

Countries Where Citrus is Reportedly Produced with Forced Labor and/or Child Labor

Citrus fruits are reportedly produced with forced labor (FL) and/or child labor (CL) in the following countries:

Belize (CL)

Turkey (CL)

Top ten countries that produce citrus worldwide (FAOSTAT 2014):

- China

- China, mainland

- Brazil

- India

- Mexico

- United States

- Spain

- Egypt

- Indonesia

- Turkey

Where are citrus fruits reportedly produced

with trafficking and/or child labor?

Citrus Production and Supply Chain

Citrus production involves five steps: selecting a favorable rootstock to plant citrus trees, planting the tree on suitable soil, watering and fertilizing the trees, protecting the trees from disease and weather, and pruning trees. Sometimes companies will contract out the harvesting of the fruits to individuals. These individuals may then sub-contract out harvesting work, leaving the company with little visibility into the harvesting process.[18]

Within the fresh fruit market, exported fruits usually pass through the packing house for washing, sorting, grading, and packing. The fruits are then sent off to the wholesale market where they are sold to consumers.[19]

How do trafficking and/or child Labor in

citrus production affect me?

The United States is one of the largest consumers of citrus fruits, oranges in particular.[20] However, in past years, citrus sales in Florida, the largest citrus producer in the United States, have declined. In 2017/2018, per capita consumption of fresh citrus fruit in the United States was 23.9 pounds.[21]

As of 2018, the United States is the third largest importer of citrus products from Belize, following France and the United Kingdom.[22]

Examples of what governments,

corporations, and others are doing:

In an effort to prevent children from missing school in order to engage in agricultural work, the Turkish government raised the age of compulsory education to 17 in 2012. The government increased the number of labor inspectors in the country by 141 and also launched new programs to address the issue of child labor.[23] In 2017, in partnership with UNICEF and the Turkish Red Crescent, the Turkish government extended its Conditional Cash Transfers for Education (CCTE) program to cover “school-age refugee children residing in Turkey under temporary/international protection,” including Syria refugee children. Under this program, if a child has attended school regularly over the course of two months, the family will receive cash support, helping to deter child labor.[24]

In Belize, there was an awareness raising campaign conducted by the Ministry of Labor and the Department of Human Services in 2011 in order to deter child labor in citrus production. The Belize government also created a 10-year National Plan of Action for Children and Adolescents starting in 2010.[25] In April of 2016, the Government of Belize committed to developing a Children’s Agenda covering 2017-2013. The framework of this agenda prioritizes the wellbeing and education of children between the ages of 0 and 19.[26] From September 2014 to July 2019, Belize was part of a United States Department of Labor funded-project to reduce child labor—the Country Level Engagement and Assistance to Reduce Child Labor II (CLEAR II) project—which supported select countries with improving legislation addressing child labor issues; improving monitoring and enforcement of laws and policies related to child labor; implementing national plans of actin on child labor; and enhancing the implementation of national and local policies and programs aimed at reducing child labor.[27]

What does trafficking and/or child labor look

like in the production of citrus?

Syrian refugees, a highly vulnerable population for a range of labor abuses,[3] are widely employed in the agriculture sector in Turkey, including in the citrus sector. These workers are generally hired in teams, or in family units, for particular agricultural jobs. There is a noted labor shortage in agricultural sectors in Turkey, including citrus.[4] Recruiters are reportedly used to hire Syrian migrants for agricultural work in Turkey, although this is not specifically tied to citrus production.[5] A team of 30 to 35 people may be hired for a day to pick a set amount of citrus, and they each receive a daily wage.[6]

In 2019, the U.S. Department of State reported that employers in the citrus industry in Belize often did not pay minimum wages and “that national and migrant workers were denied rights.”[7]

In the past, potential cases of forced labor have been identified in the U.S. citrus industry, tied to third-party labor providers engaging migrant workers.[8]

Child labor is a risk in citrus production in multiple contexts. The Child Development Foundation, a non-profit social justice organization in Belize, has identified the citrus industry as being vulnerable to child labor.[9] Children in rural areas work in citrus production either after school[10] or during their time off from school during the citrus harvest season in order to supplement their family income.[11] This type of seasonal agricultural child labor is particularly common among migrant communities working in citrus production.[12] A 2016 report found children of Syrian migrant workers, some as young as 10, harvesting citrus fruit with other workers in order to contribute to their family’s income. Syrian refugees in Turkey may also be employed to prune citrus fruit trees[13] and in citrus packing plants.[14] Internal migrant seasonal agriculture workers are also employed in citrus production in Turkey, and it is common for children to work alongside their parents and other relatives. The seasonal migration required for agricultural work can prevent these children from attending school; work in agriculture can also expose them to hazards such as pesticides.[15] Children working in citrus in the U.S. have also been identified, as children work in a variety of U.S. crops, although the scope and scale of the children working in citrus specifically has not been identified.[16]

Work in citrus production has some specific hazards which are particularly pronounced for children: work is often conducted at high heights on top of ladders; workers, including children, may also carry heavy bags and are at risk for musculoskeletal disorders.[17]

LEARN MORE

- Read an in-depth qualitative study on child labor in Belize.

- Watch a video child labor in agriculture in Brazil.

- Read an article on child laborers within Turkey’s registered workforce.

- Read a report about migrant agriculture workers in Turkey.

- Read an article about Syrian refugees working in agriculture in Turkey.

Endnotes

[2b] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2019. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-Trafficking-in-Persons-Report.pdf

[3] Business and Human Rights Resource Center. The Price You Pay: How Purchasing Practices Harm Turkey’s Garment Workers. July 2019. https://www.business-humanrights.org/sites/default/files/Turkey%20Purchasing%20Practices%20Briefing.pdf

Segal, David. Syrian Refugees Toil on Turkey’s Hazelnut Farms With Little to Show for It. New York Times. April 29, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/29/business/syrian-refugees-turkey-hazelnut-farms.html

[4] United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. TURKEY: Syrian Refugee Resilience Plan. 2018-2019.

https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/emergencies/docs/Fao-syrian-refugee-plan2018-19.pdf

[5] International Crisis Group. Turkey’s Syrian Refugees: Defusing Metropolitan Tensions. 2018. https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/western-europemediterranean/turkey/248-turkeys-syrian-refugees-defusing-metropolitan-tensions

[6] Development Workshop. Fertile Lands, Bitter Lives: The Situation Analysis Report on Syrian Seasonal Agricultural Workers in the Adana Plain. October 2016. https://www.academia.edu/30811191/Fertile_Lands_Bitter_Lives_THE_SITUATION_ANALYSIS_REPORT_ON_SYRIAN_SEASONAL_AGRICULTURAL_WORKERS_IN_THE_ADANA_PLAIN

[7] U.S. Department of State. 2018 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Belize. March 13, 2019. https://www.state.gov/reports/2018-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/belize/

[8] Coalition of Immokolee Workers. Florida Slavery: Yesterday and Today. https://www.ciw-online.org/images/slavery%20brief%20final%20photos.pdf

[9] News 5. “Working to Reduce Child Labour in Belize.” November 10, 2017. https://edition.channel5belize.com/archives/155811

[10] International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC). Internationally Recognized Core Labor Standards in Belize. Report for the WTO General Council Review of the Trade Policies of Belize. Geneva. November 5, 2010. https://www.ituc-csi.org/IMG/pdf/Belize_final.pdf

[11] UNICEF and The Government of Belize. The Situation Analysis of Children and Women in Belize 2011: An Ecological Review. July 2011. https://www.unicef.org/sitan/files/SitAn_Belize_July_2011.pdf

[12] UNICEF and The Government of Belize. The Situation Analysis of Children and Women in Belize 2011: An Ecological Review. July 2011. https://www.unicef.org/sitan/files/SitAn_Belize_July_2011.pdf

[14] Abouzeid, Rania. “Fleeing Syria, these child refugees become child laborers.” National Geographic. June 20, 2019. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/2019/06/after-fleeing-syria-young-refugees-become-youngest-laborers-feature/

[15] Support to Life and REWE Group. Seasonal Agricultural Work in Turkey: Survey Report 2014. 2014. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/57035

[16] Human Rights Watch (HRW). Fields of Peril. May 2010. https://www.hrw.org/report/2010/05/05/fields-peril/child-labor-us-agriculture

[17] Western Farms Press. “Safety Tips for a Good Citrus Harvest.” 2003. https://westernfarmpress.com/safety-tips-given-good-citrus-harvest

[18] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Citrus Fruit. 2009. UNCTAD.org

[19] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Citrus Fruit. 2009. UNCTAD.org

[20] Boriss, Haley. Citrus. Agricultural Resources Marketing Center. https://www.agmrc.org/commodities__products/fruits/citrus/citrus-profile/

[21] “Per capita consumption of fresh citrus fruit in the United States from 2000/01 to 2017/18.” Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/257189/per-capita-consumption-of-fresh-citrus-fruit-in-the-us/

[22] UN Comtrade Database. Belize Citrus Exports. https://comtrade.un.org/ 2018.

[23] U.S. Department of Labor. Turkey. 2015. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor/turkey

[24] UNICEF. “The Conditional Cash Transfer for Education (CCTE) Programme.” https://www.unicef.org/turkey/en/conditional-cash-transfer-education-ccte-programme

[25] International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC). Internationally Recognized Core Labor Standards in Belize. Report for the WTO General Council Review of the Trade Policies of Belize. Geneva. November 5, 2010. https://www.ituc-csi.org/IMG/pdf/Belize_final.pdf

[26] Ministry of Human Development Social Transformation and Poverty Alleviation. Children’s Agenda 2017-2030. 2017. https://humandevelopment.gov.bz/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Childrens-Agenda-2017-2030.pdf

[27] U.S. Department of Labor. “Country Level Engagement and Assistance to Reduce Child Labor II (CLEAR II).” https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/country-level-engagement-and-assistance-reduce-child-labor-ii-clear-ii