Commodity Atlas

Cattle

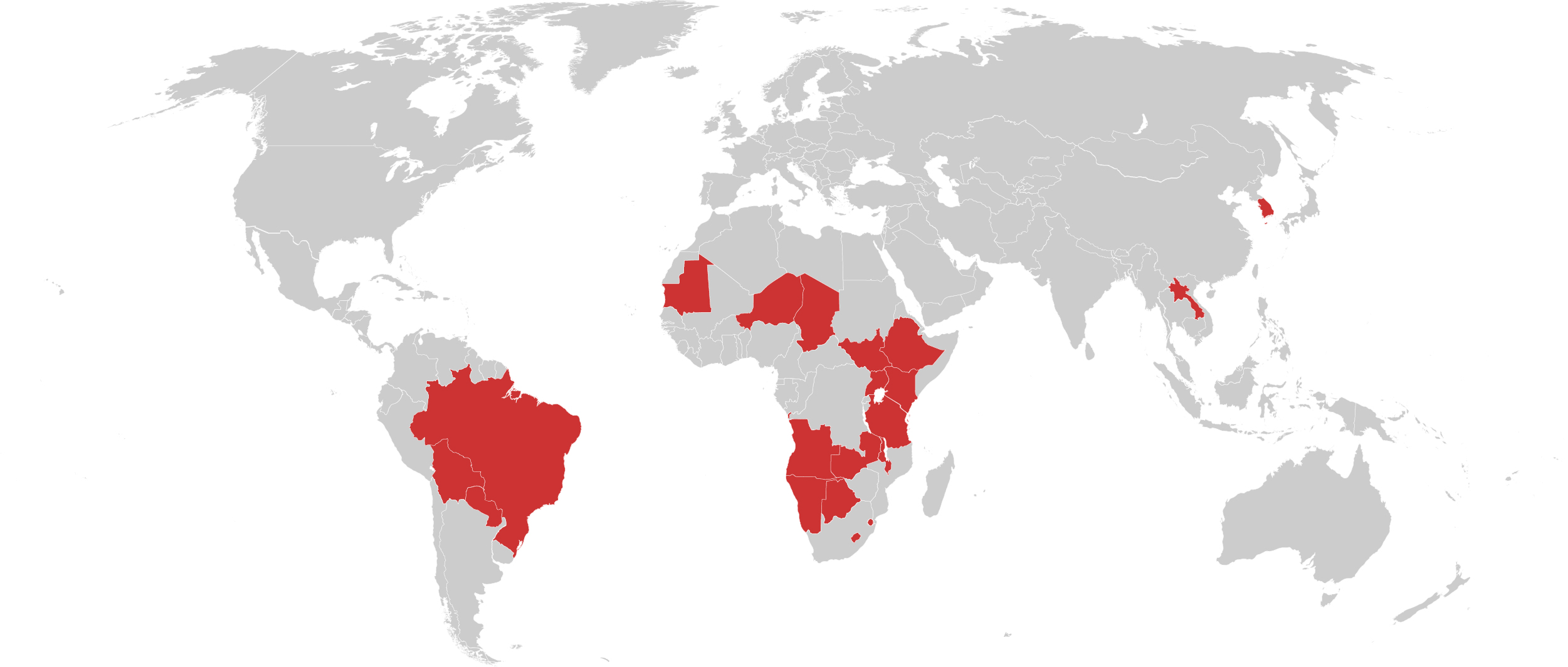

Countries Where Cattle and/or Beef are Reportedly Produced with Forced Labor and/or Child Labor

Cattle and beef are reportedly produced with forced labor (FL) and/or child labor (CL) in the following countries:

Cattle:

Angola (FL)

Bolivia (FL)

Brazil (FL, CL)

Botswana (FL, CL)

Chad (FL, CL)

Eswatini (FL)

Ethiopia (CL)

Kenya (FL)

Korea, Republic of (FL)

Laos (FL)

Lesotho (CL)

Malawi (FL)

Mauritania (FL, CL)

Namibia (FL, CL)

Niger (FL)

Paraguay (FL, CL)

South Sudan (FL, CL)

Tanzania (FL, CL)

Uganda (FL, CL)

Zambia (CL)

Beef:

Brazil (CL)

Top ten countries that export beef worldwide (UN Comtrade 2018)1:

Beef (frozen):

1. Brazil

2. Australia

3. United States

4. India

5. New Zealand

6. Uruguay

7. Argentina

8. Paraguay

9. Canada

10. Poland

Beef (chilled):

1. United States

2. Netherlands

3. Australia

4. Ireland

5. Canada

6. Poland

7. Germany

8. Mexico

9. France

10. Brazil

Top ten countries that import beef (UN Comtrade 2018)2:

Beef (frozen):

1. China

2. United States

3. Hong Kong

4. Republic of Korea

5. Japan

6. Egypt

7. Russia

8. Taipei

9. Indonesia

10. Malaysia

Beef (chilled):

1. United States

2. Japan

3. Italy

4. Netherlands

5. Germany

6. United Kingdom

7. France

8. Chile

9. Republic of Korea

10. Mexico

[1,2] International Trade Center (ITC Calculations based on UNCOMTRADE Statistics). https://www.intracen.org/

Where are cattle and beef products reportedly produced with trafficking and/or child labor?

The 2018 U.S. Department of Labor’s List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor indicates that cattle is produced with forced labor in Bolivia and Niger, and with child labor in Chad, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Lesotho, Mauritania, Namibia, Uganda, and Zambia.[2b] The list states that both forced labor and child labor are present within the cattle sectors of Brazil, Paraguay. Beef has also been found to have been produced with child labor in Brazil.[3]

Botswana, Brazil, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Kenya, Paraguay, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia are listed as Tier 2 countries by the U.S. Department of State 2018 Trafficking in Persons Report. Angola, Chad, Eswatini, and South Sudan are Tier 2 Watch List countries. Laos and Mauritania are Tier 3 countries, while the Republic of Korea is a Tier 1 country.[4]

How do trafficking and/or child labor in

cattle ranching affect me?

Products from cattle ranching include beef and leather. Leather is used in a variety of consumer goods from shoes to couches. Furthermore, cattle ranching is known to be directly linked to deforestation and environmental degradation.[22]

Cattle production and supply chain:

The United States is the “world’s largest fed-cattle industry,” and although the United States is one of the largest producers of beef, it is a net beef importer. Most beef produced and exported from the United States is grain-fed, high quality cuts. Most beef that the United States imports is lower value, grass-fed beef used mainly for processing, primarily as ground beef.[20] According to 2013 numbers from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the United States imports beef and veal mostly from New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and Mexico. The United States exports beef and veal to Japan, Mexica, Canada, and South Korea.[21]

Examples of what governments, corporations, and others are doing:

Brazil has often been cited as an example of effective government action against forced labor. The ILO has praised Brazil’s measures to combat forced labor. It is important to note that the Brazilian concept of slave labor is broader than the ILO’s definition of forced labor.[23] Article 149 of Brazil’s Penal Code defines slave labor as, “Reducing someone to a condition analogous to that of a slave, namely: subjecting a person to forced labor or to debilitating workdays, or subjecting such a person to degrading working conditions or restricting, in any manner whatsoever, his mobility by reason of a debt contracted in respect to the employer or a representative of that employer.” Slave labor may thus include some or all of the following elements: forced labor, debilitating workdays, degrading working conditions, and restrictions on freedom of movement, including through debt bondage. All of these elements are, at the least, ILO indicators of forced labor. However, while the existence of one of these elements would meet the definition of slave labor under Brazilian law, the existence of one indicator of forced labor alone would not meet the ILO’s criteria for identifying forced labor in practice.[24] Therefore, it is important to note that while some cases of “slavery” – the terminology most commonly used in media reports and NGO advocacy efforts in Brazil – may in fact constitute forced labor ,and at the least indicate a high level of risk of forced labor, not all of the cases of slavery necessarily rise to the level of forced labor.

In 2011, the state of Sao Paulo created a Commission for the Eradication of Forced Labor. The group, also known as Coetrae, is tasked with evaluating and tracking cases of forced labor, monitoring compliance with forced labor laws, conducting research, and coordinating with the Secretariat of Justice and NGOs on combatting forced labor.[25] In addition, the government has created a National Pact for the Elimination of Slavery, which brings the government, the ILO, NGOs, and companies together to combat forced labor. Over 400 companies have signed on, representing almost 30 percent of Brazil’s GDP, thereby committing not to buy products derived from forced labor.[26]

In November 2003, the Minister of National Integration signed a decree containing a list of 52 individuals and entities that use or have used slave labor. The individuals and entities on the biannually updated “dirty” list” are barred from receiving national subsidies or tax exemptions and from engaging in financial arrangements with a number of public financial institutions. The Bank of Brazil denies financing to landowners who employ slave labor and the Ministry of National Integration recommended that private sector lenders deny them financing as well.[27] By the end of 2013, there were 380 companies on the list.[28] However, CNN reported in 2017 that recent versions of the list had been blocked or delayed.

The Brazilian Roundtable on Sustainable Livestock is a multi-stakeholder initiative intended to improve standards across the Brazilian cattle and livestock sectors. In 2018, the Roundtable launched a database of farms that also includes responsibility principles for management systems, community, workers, environment and value chains. Participating farmers are asked to undertake a self-assessment.[29]

What does trafficking and/or child labor in

cattle ranching look like?

Labor trafficking in cattle ranching varies from country to country. In Bolivia, the International Labor Organization (ILO), Verité, and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights have documented the existence of debt peonage on cattle ranches in the Bolivian Chaco.[5] In 2010 and 2011, Verité conducted research on indicators of forced labor in cattle production in the Chaco region of Bolivia. Researchers found the presence of indicators including the threat of physical violence, sexual violence, and loss of social status, as well as excessive working hours, lack of days off, subminimum wages, hazards to worker health, and child labor. In the Chaco region of Bolivia, the indigenous Guaraní who work on haciendas or as self-employed cattle ranchers on communal lands are particularly vulnerable. Researchers found that many wage workers are indebted to their employers, causing confinement to the worksite and withholding of wages. Workers are also paid well below the minimum wage and are susceptible to injuries from slash and burn agricultural techniques. Indicators of forced labor are also present for self-employed workers who work on communal lands. For these workers, excessive hours are compulsory especially in the area of animal husbandry which requires daily work without rest. Those who do not work are subject to removal from the community which would include loss of social status, land, job or even their home. Because work is done as a family unit on these communal lands, child labor is an extremely common practice.[6]

In Brazil, cattle ranching accounts for over 60 percent of the companies on the “dirty list” of groups using forced labor.[7] As in other goods produced in Brazil, labor trafficking results from young men being brought by brokers to rural plantations where they then enter into debt bondage.[8] Cattle ranching may encompass a variety of activities, from clearing land for pasture to monitoring livestock to handling the production of goods, and has been linked to environmental devastation in the Brazilian Amazon.[9] As of 2017, over 50,000 workers have been rescued from what Brazil defines as conditions of slave labor, with one third of the workers rescued coming from cattle ranches in remote areas.[10] In 2017, CNN reported on a case of ranchers who were provided food by the ranch owner, the cost of which was deducted from their wages, leaving them in a cycle of debt. [11] These workers had not been paid in two years.[12]

The 2018 U.S. Department of State reports that Angolan boys are taken to Namibia for forced labor in cattle herding.[13]

In Chad, child herders, some of whom are victims of forced labor, follow traditional routes for grazing cattle and are known to cross ill-defined international borders into Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Sudan, and Nigeria.[14] Some of these children are reportedly sold in markets for use in cattle or camel herding or they may be subjected to forced labor by military or local government officials.[15] In Botswana, some children from poor families in isolated rural communities may migrate to live with wealthier extended family members and some of their work may include cattle herding.[16] In Mauritania, inherited slavery may force individuals to work as unpaid cattle herders.[17]

Children are often engaged in herding, which involves keeping groups of animals together, and is common in pastoral agricultural and nomadic societies. Livestock tasks tend to be distributed along gender lines: cattle herding is generally a task for men and boys, and herding activities can begin as young as five years of age. Culturally, herding can be seen as an opportunity to contribute to family income and to earn income. While light work accompanying family members may be appropriate, working with cattle can carry a variety of health and safety risks. These include animal-related disease, long hours in extreme weather conditions, dust inhalation, confrontation with cattle raiders, injuries from handing livestock and tools, and musculoskeletal disorders.[18]

In the Republic of Korea, physically or intellectually disabled men are reportedly vulnerable to exploitation and have been forced to work on cattle farms where they experience verbal and physical abuse, non-payment of wages, long work hours, and poor working and living conditions.[19]

LEARN MORE

Endnotes

[1b] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[2b] U.S. Department of Labor. 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. 2018. https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ilab/ListofGoods.pdf

[3] U.S. Department of Labor. 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. 2018. https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ilab/ListofGoods.pdf

[4] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[5] Garcia, Eduardo. “Bolivian Guarani Resist Forced Labor on Ranches.” Reuters. June 19, 2008.

https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSN18254614.

International Labor Organization (ILO). A Global Alliance against Forced Labour: Global Report under the Follow-up to the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. 2005. https://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc93/pdf/rep-i-b.pdf

Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chains of Brazil-Nuts, Cattle, Corn, and Peanuts in Bolivia. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Bolivia%20Brazil-nut%2C%20Cattle%2C%20Corn%2C%20and%20Peanut%20Sectors__9.19.pdf

[6] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chains of Brazil-Nuts, Cattle, Corn, and Peanuts in Bolivia. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Bolivia%20Brazil-nut%2C%20Cattle%2C%20Corn%2C%20and%20Peanut%20Sectors__9.19.pdf

[7] Costa, Patricía Trindade Maranhão. Fighting Forced Labor: The Example of Brazil. Geneva: International Labor Office. 2009. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—declaration/documents/publication/wcms_111297.pdf

[8] Darlington, Shasta et al. “Slavery in the Amazon: Thousands forced to work on Brazil’s cattle ranches.” CNN. May 11, 2017. https://www.cnn.com/2017/04/26/americas/brazil-amazon-slavery-freedom-project/index.html

[9] Hoelle, Jeffrey. Jungle Beef: consumption, production and destruction, and the development process in the Brazilian Amazon. Journal of Political Ecology, Vol. 24. 2017.

[10] Darlington, Shasta et al. “Slavery in the Amazon: Thousands forced to work on Brazil’s cattle ranches.” CNN. May 11, 2017. https://www.cnn.com/2017/04/26/americas/brazil-amazon-slavery-freedom-project/index.html

[11] Darlington, Shasta et al. “Slavery in the Amazon: Thousands forced to work on Brazil’s cattle ranches.” CNN. May 11, 2017. https://www.cnn.com/2017/04/26/americas/brazil-amazon-slavery-freedom-project/index.html

[12] Darlington, Shasta et al. “Slavery in the Amazon: Thousands forced to work on Brazil’s cattle ranches.” CNN. May 11, 2017. https://www.cnn.com/2017/04/26/americas/brazil-amazon-slavery-freedom-project/index.html

[13] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[14] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[15] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[16] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[17] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[18] Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO). Children’s Work in the Livestock Sector: Herding and Beyond. 2012. https://www.fao.org/docrep/017/i3098e/i3098e.pdf

[19] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[20] U.S. Department of Agriculture. Cattle & Beef. August 22, 2018. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/animal-products/cattle-beef/sector-at-a-glance/

[21] U.S. Department of Agriculture. Beef and Veal: Annual and Cumulative Year-to-Date US Trade. June 7, 2019. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/livestock-and-meat-international-trade-data/

[22] “New report examines drivers of rising Amazon deforestation on country-by-country basis.” Mongabay. 2019. https://news.mongabay.com/2019/05/new-report-examines-drivers-of-rising-amazon-deforestation-on-country-by-country-basis/

[23] U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Democracy. Human Rights and Labor. Country Reports on Human Labor Rights Practices 2013. https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/#wrapper

[24] International Labour Organization. Hard to See, Harder to Count Survey Guidelines to Estimate Forced Labour of Adults and Children. 2011.

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/–declaration/documents/ publication/wcms182096.pdf

[25] U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 2011 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – Brazil. https://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2010/wha/154496.htm.

U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 2009 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. https://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/.

U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Democracy. Human Rights and Labor. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2014. https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/index.htm#wrapper

[26] Kelly, Annie. “Brazil’s ‘dirty list’ names and shames companies involved in slave labor.” July 24, 2013.

[29] University of Nottingham. Tackling slavery in supply chains: lessons from Brazilian-UK beef and timber. 2019. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/beacons-of-excellence/rights-lab/mseu/mseu-resources/2019/march/emberson-tackling-slavery-in-supply-chains.pdf