Commodity Atlas

Coffee

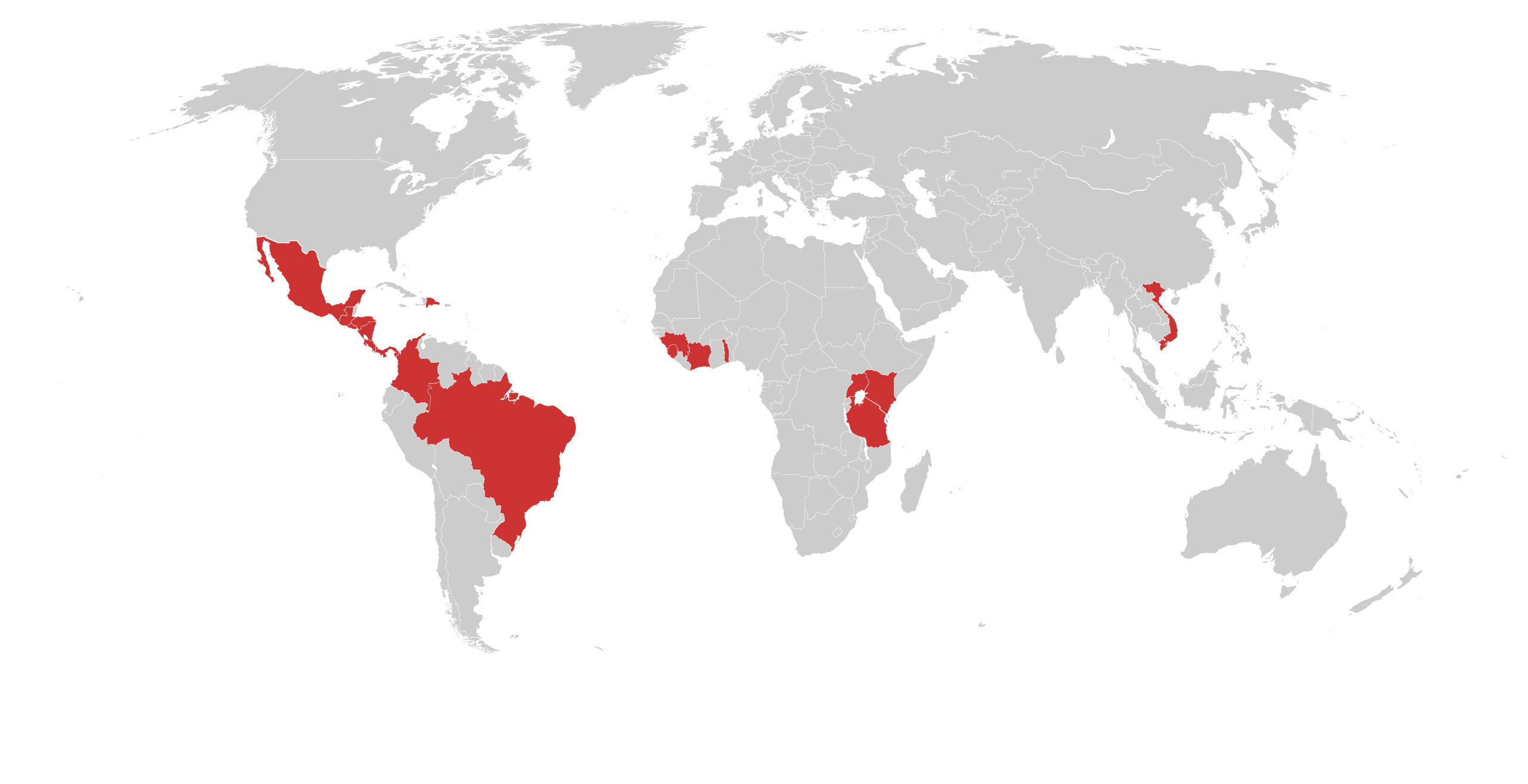

Countries Where Coffee is Reportedly Produced with Forced Labor and/or Child Labor

Coffee is reportedly produced with forced labor (FL) and/or child labor (CL) in the following countries:

- Brazil (CL)

- Côte d’Ivoire (CDI) (FL, CL)

- Colombia (CL)

- Costa Rica (CL)

- Dominican Republic (CL)

- Guatemala (CL)

- Guinea (CL)

- Honduras (CL)

- El Salvador (CL)

- Kenya (CL)

- Mexico (FL, CL)

- Nicaragua (CL)

- Panama (CL)

- Sierra Leone (CL)

- Tanzania (CL)

- Togo (FL)

- Uganda (CL)

- Vietnam (CL)

Top ten countries that produce coffee worldwide (FAOSTAT 2017):

- Brazil

- Vietnam

- Colombia

- Indonesia

- Honduras

- Ethiopia

- Peru

- India

- Guatemala

- Uganda

Where is coffee reportedly produced with trafficking and/or child labor?

The U.S. Department of Labor’s 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor indicates that coffee is produced with forced labor and child labor in Côte d’Ivoire (CDI) and with child labor in Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Guinea, Honduras, El Salvador, Kenya, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda, and Vietnam.[2b]

Colombia is listed as a Tier 1 country by the U.S. Department of State 2018 Trafficking in Persons Report. Brazil, Costa Rica, Cote d’Ivoire, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, Kenya, Mexico, Panama, Tanzania, Uganda, and Vietnam are listed as Tier 2 countries. Guatemala, Guinea, Nicaragua, Sierra Leone, and Togo are listed as Tier 2 Watch List Counties.[3]

How do trafficking and/or child labor in coffee production affect me?

Coffee is one of the most commonly consumed beverages in the world. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), coffee is the second most traded commodity world-wide after oil.[28] As of 2017, The United States imported 19.3 percent of all of the world’s coffee imports. The United States imports the largest amounts of coffee from Columbia, Brazil, Canada, Vietnam, Guatemala, and Indonesia.[29]

Examples of what governments, corporations, and others are doing:

A number of sustainability certifications cover coffee, including Common Code for the Coffee Community (4C), Fairtrade, and Rainforest Alliance. Some companies have their own certifications and standards, such as Nespresso AAA Sustainable Quality and Starbucks Coffee and Farmer Equity (C.A.F.E.) Practices. Approximately 40 percent of global coffee production was under voluntary certification in 2012.[30] These certifications have varying levels of social standards, and many do not cover common indicators of trafficking, such as recruitment fees, document retention, indebtedness, and restrictions on workers’ freedom of movement. Some, such as Organic certification, include no standards on social compliance, and therefore provide no safeguards against labor violations.[31] Furthermore, some certifications utilize a “square root” methodology to select farms for inspections, meaning that in large markets, just 0.5 percent of farms are inspected every three years, meaning that it would take hundreds of years to inspect all of the farms in the supply chain.[32]

Verité research, along with investigations carried out by Danwatch, Finnwatch, Repórter Brasil, and Univision/The Weather Channel have detected child labor, trafficking indicators, and other violations on certified farms, demonstrating the importance of monitoring for compliance.[33] In 2018 the Brazilian Ministry of Labor detected labor abuses on a certified farm in rural Minas Gerais state and rescued workers from slavery-like conditions there.[34]

In 2015, Keurig Dr. Pepper (KDP), a coffee and beverage company then known as Keurig Green Mountain, partnered with Verité to research recruitment and working conditions and worker needs in the Guatemalan coffee sector and to conduct trainings for workers, government officials, local NGO representatives, and coffee producers, traders and brands. The project, with funding from both Keurig and the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, also included mapping Keurig’s supply chain and building a grievance reporting and information dissemination (GRID) system to monitor and improve labor practices, which was utilized by over 1,000 workers, and trainings of over 500 workers, along with government officials, civil society organizations, and coffee producers and traders[35] Nestlé and Jacobs Douwe Egberts (JDE), which together account for almost half of the global coffee market, have responded to allegations of forced labor on farms they source from by updating their human rights policies and requiring compliance from their suppliers.[36]

The U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs is currently funding a project to address child labor and forced labor in the coffee supply chain in Honduras. This project is designed to “help businesses establish systems to prevent, detect, and eliminate child labor and other forms of labor exploitation form their supply chains.”[37]

What does trafficking and/or child labor in coffee production look like?

Few large-scale studies have been carried out on human trafficking in the coffee sector; however, in-depth research carried out by Verité, as well as anecdotal reports, confirm its existence in multiple countries. Verité research has identified indicators of forced labor in the Guatemalan and Mexican coffee sectors.[4] Investigations by Danwatch and Finnwatch have uncovered indicators of forced labor in the Brazilian coffee sector,[5] while a 2016 Danwatch report found indicators of forced labor in the Guatemalan coffee sector,[6] and a Univision/Weather Channel documentary found child labor, degrading living conditions, and a lack of inspections in the Mexican coffee sector.[7] In 2018, investigations of two coffee farms in Brazil conducted by the Brazilian Ministry of Labor found “conditions analogous to slavery,” resulting in the rescue of 33 workers.[8] Research conducted by Oxfam has identified coffee harvesters in Kenya under 15 years of age, and the ILO has reported child labor in the Kenyan coffee sector, particularly on commercial plantations.[9]

Large coffee plantations may recruit workers via labor brokers, a practice that leaves workers vulnerable to deceptive recruitment, document retention, debt bondage, and other indicators of forced labor. Verité research has documented these practices on coffee plantations in Guatemala. .[10] In Brazil, Mexico, and Guatemala, research has found that migrant workers on coffee plantations are often hired as temporary workers who lack formal work contracts, increasing their vulnerability.

Minimum wage violations are common, even on farms producing gourmet coffee.[11] Other wage-related and working hour-related violations can also occur. For example, while the Guatemalan Labor Code requires workers to be paid every 15 days, Verité research found that coffee workers were often paid every month or at the end of the harvest, which encouraged the workers to stay on the estates until the harvest season was over and that many workers were paid according to a quota system.[12] In Brazil, workers have reported being forced to buy their own equipment resulting in debt to the farm owner, working extremely long work days for weeks on end without a day off.[13] Coffee workers may also be subjected to threats, verbal abuse, and unhygienic living conditions without access to potable water or shade on coffee estates.[14]

Smallholder coffee farms rely heavily on family labor, and children are likely to work on family farms. On larger estates, children may work alongside their parents either to supplement their families’ income, to help parents meet their production quotas, or because the children of migrant parents have nowhere else to go during the day if they are not enrolled in school.[15] Children involved in coffee production take on a variety of tasks including pruning trees, weeding, fertilizing, picking and sorting berries, and transporting beans and other supplies. Work in coffee production leaves children vulnerable to injuries from tools and equipment, hearing loss due to machinery, musculoskeletal injuries, respiratory illness, pesticide exposure, sun and heat exposure, snake and insect bites, long working hours, and withdrawal from school.[16]

A 2016 study by Finnwatch reported that child labor, including among children as young as five to six years old, appeared to be common on coffee plantations visited in Honduras.[17] Working children in that study were not the children of the farm owners, but instead were hired directly or worked alongside their parents.[18] Almost all coffee workers interviewed by Verité in Guatemala (98.9 percent) reported that the estates on which they were last employed used child laborers, some as young as five years old.[19]

Coffee production and supply chain:

Most coffee, by some estimates up to 80 percent, is grown by smallholder farms.[20] Coffee is also grown on larger plantations that employ both permanent and temporary labor.[21] Coffee production provides a livelihood for over 26 million people worldwide.[22]

Coffee plants bear fruit approximately three to four years after planting, and the fruit turns red when it is ready to be harvested. Harvesting the coffee bean is labor intensive. Beans are either “strip picked” or “selectively picked.” If beans are strip picked, all beans are harvested at one time. When beans are selectively picked, only the ripe berries are picked. Picking selectively is more labor intensive, and often reserved for higher quality beans. There are one or two major harvests per year and pickers average approximately 100-200 pounds of coffee beans a day. Many workers are normally paid by the weight of beans picked.[23]

After coffee is harvested, the seeds are dried either by the sun or, on more mechanized plantations, by machine. Beans are then hulled, sorted, and graded for quality before being roasted. Labor trafficking may occur at all stages of production, but it is most likely to occur during harvesting.

Coffee production is sensitive to weather conditions and various diseases, and the resulting market is characterized as unstable and volatile with large price fluctuations.[24] Coffee prices are set by the New York “C” contract market. Changes in global supply, trading, and speculation can all lead to fluctuating prices. Droughts or other supply chain disruptions – particularly in Brazil, the world’s largest producer – increase the price. Specialty coffee may be imported at a higher negotiated price, but according to Global Exchange, farmers often do not benefit from this premium, which disincentives increased quality in production.[25] The volatility of the coffee market can put strong downward pressure on coffee farmers and plantations to decrease all input costs, including labor, which is often the only input over which they have control. Labor reportedly accounts for up to 70 percent of production costs.[26] When prices are particularly low, farmers sell their beans for less than the cost of production, leaving many coffee producing families far below the poverty line.[27]

LEARN MORE

Endnotes

[2b] U.S. Department of Labor. 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. 2018. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/reports/child-labor/list-of-goods?items_per_page=All&combine=coffee

[3] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2018. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/282798.pdf

[4] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Coffee in Guatemala. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Guatemala%20Coffee%20Sector__9.16.pdf

[5] FinnWatch. Brewing up a sustainable coffee supply chain. April 2016. https://www.finnwatch.org/images/pdf/FW_Coffee_report_18102016.pdf

DanWatch. You may be drinking coffee grown under slavery-like, life-threatening conditions. March 10, 2016. https://old.danwatch.dk/en/undersogelse/bitter-kaffe/

[6] Hjerl Hansen, Julie. Bitter Coffee – Guatemala. Danwatch. September 8, 2016. https://www.danwatch.dk/en/undersogelse/bitter-coffee-guatemala/

[7] The Weather Channel and Telemundo. “The Source: The human cost hidden within a cup of coffee.” January 19, 2017. https://thesourcefilm.com/

[8] Penha, Daniela. “Slave labor found at Starbucks-certified Brazil coffee plantation.” Mongabay. September 18, 2018. https://news.mongabay.com/2018/09/slave-labor-found-at-starbucks-certified-brazil-coffee-plantation/

[9] Oxfam. The Coffee Market: A Background Study. 2001. https://www.oxfamamerica.org/static/media/files/mugged-full-report.pdf.

Mueithi, Leopold. International Labour Organization. Coffee in Kenya: Some challenges for decent work. 2008. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ba34/dc1f9d644d2d627a3f7647f0cf227014c9e4.pdf.

[10] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Coffee in Guatemala. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Guatemala%20Coffee%20Sector__9.16.pdf

[11] Finnwatch. Brewing up a sustainable coffee supply chain. April 2016. https://www.finnwatch.org/images/pdf/FW_Coffee_report_18102016.pdf

[12] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Coffee in Guatemala. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Guatemala%20Coffee%20Sector__9.16.pdf

[13] Penha, Daniela. “Slave labor found at Starbucks-certified Brazil coffee plantation.” Mongabay. September 18, 2018. https://news.mongabay.com/2018/09/slave-labor-found-at-starbucks-certified-brazil-coffee-plantation/

[14] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Coffee in Guatemala. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Guatemala%20Coffee%20Sector__9.16.pdf

Lopes, Marina. “The hidden suffering behind the Brazilian coffee that jump-starts American mornings.” The Washington POst. August 31, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/the-hidden-suffering-behind-the-brazilian-coffee-that-jump-starts-american-mornings/2018/08/30/e5e5a59a-8ad4-11e8-9d59-dccc2c0cabcf_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.bf657e39651c

Finnwatch. Brewing up a sustainable coffee supply chain. April 2016. https://www.finnwatch.org/images/pdf/FW_Coffee_report_18102016.pdf

[15] Global Exchange. Coffee FAQ. https://www.globalexchange.org/fairtrade/coffee/faq#1

Fair Trade USA. Child Labor in Coffee Supply Chains. January 27, 2017. https://fairtradeusa.org/press-room/press_release/child-labor-coffee-supply-chains https://fairtradeusa.org/press-room/press_release/child-labor-coffee-supply-chains

[16] International Labor Organization (ILO). Safety and Health Fact Sheet: Hazardous Child Labour in Agriculture: Coffee. 2004.

Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Coffee in Guatemala. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Guatemala%20Coffee%20Sector__9.16.pdf

[17] Finnwatch. Brewing up a sustainable coffee supply chain. April 2016. https://www.finnwatch.org/images/pdf/FW_Coffee_report_18102016.pdf

[18] Finnwatch. Brewing up a sustainable coffee supply chain. April 2016. https://www.finnwatch.org/images/pdf/FW_Coffee_report_18102016.pdf

[19] Verité. Research on Indicators of Forced Labor in the Supply Chain of Coffee in Guatemala. 2012. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/Research%20on%20Indicators%20of%20Forced%20Labor%20in%20the%20Guatemala%20Coffee%20Sector__9.16.pdf

[20] Oxfam. Grounds for Change. April 2006. https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/coffee.pdf

Fair Trade. “Coffee Farmers.” https://www.fairtrade.org.uk/Farmers-and-Workers/Coffee

[21] Finnwatch. Brewing up a sustainable coffee supply chain. April 2016. https://www.finnwatch.org/images/pdf/FW_Coffee_report_18102016.pdf

[22] International Coffee Organization (ICO). Employment generated by the coffee sector. 2010. https://www.ico.org/documents/icc-105-5e-employment.pdf

[23] National Coffee Association. 10 Steps to Coffee from Seed to Cup. https://www.ncausa.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=69

[24] Fair Trade. “Coffee Farmers.” https://www.fairtrade.org.uk/Farmers-and-Workers/Coffee

Oxfam. Grounds for Change. April 2006. https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/coffee.pdf

[25] Global Exchange. Coffee FAQ. https://www.globalexchange.org/fairtrade/coffee/faq#1

[26] Fair Trade USA. Child Labor in Coffee Supply Chains. January 27, 2017. https://fairtradeusa.org/press-room/press_release/child-labor-coffee-supply-chains

[27] International Labor Organization (ILO). Safety and Health Fact Sheet: Hazardous Child Labour in Agriculture: Coffee. 2004.

[28] UN Conference on Trade and Development. Commodities Atlas: Coffee. 2004. https://www.unctad.org/en/docs/ditccom20041ch4_en.pdf

[29] International Trade Center (ITC Calculations based on UNCOMTRADE Statistics). https://www.trademap.org

[30] Potts, Jason; Lynch, Matthew; Wilkings, Ann; Huppé, Gabriel; Cunningham, Maxine, and Vivek Voora. The State of Sustainability Initiatives Review: Standards and the Green Economy. International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). 2014.

[31] Specialty Coffee Association. Sustainable Coffee Certifications: A Comparison Matrix. 2009. https://www.scaa.org/PDF/SustainableCoffeeCertificationsComparisonMatrix.pdf

[32] The Weather Channel and Telemundo. “The Source: The human cost hidden within a cup of coffee.” January 19, 2017. https://thesourcefilm.com/

[33] Finnwatch. Brewing up a sustainable coffee supply chain. April 2016. https://www.finnwatch.org/images/pdf/FW_Coffee_report_18102016.pdf

[34] Penha, Daniela. “Slave labor found at Starbucks-certified Brazil coffee plantation.” Mongabay. September 18, 2018. https://news.mongabay.com/2018/09/slave-labor-found-at-starbucks-certified-brazil-coffee-plantation/

[35] Verité. Improving Supply Chain Transparency, Monitoring and Accountability in Guatemala’s Coffee Sector. Vision. July 2015. https://verite.org/improving-supply-chain-transparency-monitoring-and-accountability-in-guatemalas-coffee-sector/

[36] DanWatch. You may be drinking coffee grown under slavery-like, life-threatening conditions. March 10, 2016. https://old.danwatch.dk/en/undersogelse/bitter-kaffe/

[37] U.S. Department of Labor. “Addressing Child Labor and Forced Labor in the Coffee Supply Chain in Honduras.” https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/addressing-child-labor-and-forced-labor-coffee-supply-chain-honduras